HOW BELLY DANCING SAVED MY MARRIAGE

I find the darnedest things at my local swap shop

by Don Stradley

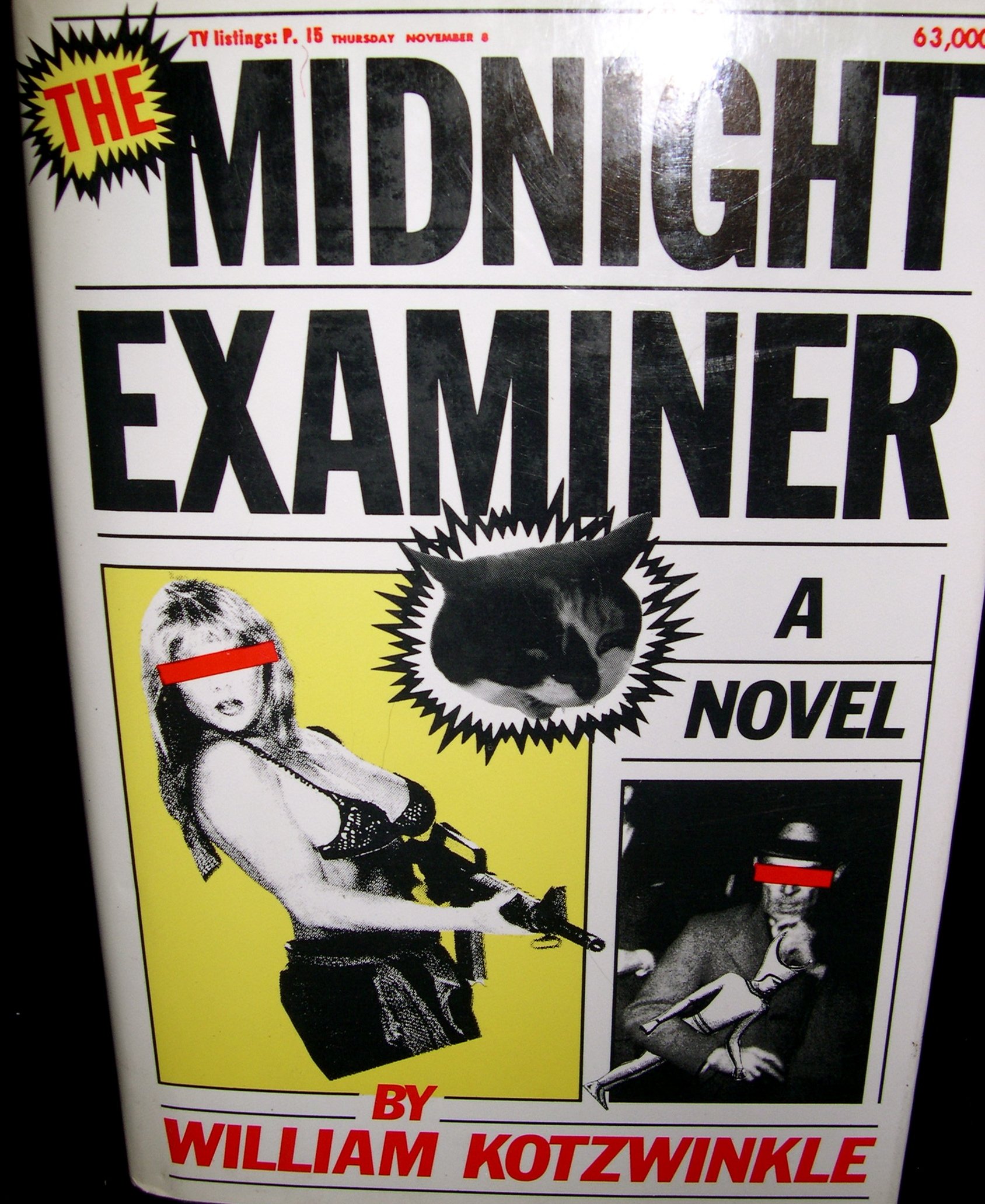

William Kotzwinkle is one of those writers - as quaint and precious as a scented candle, a name that meant a lot to college kids during the 1970s and '80s, a kind of less threatening Kurt Vonnegut, utterly convinced that satire was some kind of thorny cudgel - that I never quite got. He's in good company, because I never got Saul Bellow or Theodore Dreiser, either. I once crapped out in the middle of a John Le Carre novel because there were too many characters in it. Yet, I was always touched by the people who loved Kotzwinkle. He was their dry-witted avenger, their cuddly, slightly skewed hippie uncle figure who won awards and, shock of all shocks, was hired to write the novelization of ET, The Extraterrestrial, which for a writer whose name rhymed with "twinkle," as in "Twinkle twinkle little star," seemed beautifully appropriate. I recently found a copy of The Midnight Examiner, Kotzwinkle's 1989 send up of the supermarket tabloid industry, and though I still don't quite get him, I like him a bit more. Like the neighbor who annoys you with his opera music, he's not so bad if you get to know him.

It takes no time at all for us to understand the lightly cynical world of The Midnight Examiner. The worn out hacks at Chameleon Publications, a New York group responsible for a line of magazines with names like Macho Man and Knockers, churn out stories about plastic surgery gone awry, dead people being eaten by their cats, and my favorite, a little girl who has a UFO stuck in her uterus. The staff dreams of L.A., where "the face lift hospitals have valet parking," but despite assembling portfolios for more highbrow magazines, they know they're not getting out of their world of alien hookers. The style here is newsroom farce, His Girl Friday if Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell were bitter, hopeless alcoholics, with Kotzwinkle spinning out the dialogue as if he'd just seen a late night showing of Room Service, or worse, an episode of M.A.S.H. where Alan Alda does his Groucho act. The hybrid of newsroom razzle with tabloid schlock must've been tempting, but wading through it becomes a chore.

There's also a funny bit where a story about an exploding vibrator is squashed because one of Chameleon's chief advertisers is a company that manufactures vibrators. And there's a guy who gets a job as an editor based on his once writing a series of prank letters to the Village Voice. There's an inspired moment where a writer talks proudly about meeting a reader who truly loves the stories from Chameleon Publications, describing them as something like aspirin. When a co-worker questions if so many aspirins are good for a person, the writer responds, "If you've got a headache that won't quit, they are." And of course, the senior members of the staff fear aging. "I'm never going to look at my old movie magazines again," says one. "It's a shock to the system, seeing June Allyson as a young girl." But Kotzwinkle is actually better when he puts his humor aside and focuses on the story's underlying theme: the vanishing of New York.

The Manhattan of the 1980s was an unpleasant place, and The Midnight Examiner is bursting with mobsters, crackheads, voodoo queens, and delusional war veterans. Still, the memory of better days days lingered. "If you turn and look back in the twilit hour," Kotzwinkle writes, "you can see the old ghosts of Manhattan pulling up in their horse drawn carriages." Nowadays, I suppose you have to grind your way through the annoying tourists, with hopes of seeing the ghosts of old crackheads. Ultimately, Kotzwinkle has little to say about the milieu of cheapo magazines and the people who make them. Now and then, though, he hits a perfect note, like when the staff goes to lunch in Chinatown. "We turned on Twenty eighth, past windows full of jade turtles, ivory unicorns, and turquoise horses whose bridles sparkled with little gem stones. Fate had cut us off from the prestige and perks of the regular corporate world, but as a kind of compensation we, like these supernatural creatures, lived in an arcade of dreams, turning out fairy tales for the modern reader." This says more than Kotzwinkle's tired slapstick, as does a character quietly grousing that Chameleon magazines are never in the reception area of his psychiatrist's office.

No comments:

Post a Comment