Friday, March 31, 2017

SMALL TOWN MURDER SONGS

There's something about Walter the police chief that isn't right. As played by Peter Stormare in Small Town Murder Songs, he's a bit of a geezer. When we see him in his street clothes he looks like an older man who should be sitting on his front porch, waving to the neighbor kids. But in his police uniform he swaggers like a Nazi ready to stomp someone's head. There's violence in his past, and the whole town knows it.

The movies are loaded with conflicted cops. They're a staple of film noir, and the better police dramas of the '60s and '70s. The citizens of this small Ontario town refer to Walter by name, which shows that he's lost some of their respect. In an early scene, a prefab house is being hauled away. Walter drives slowly behind it, nodding at people on the sidewalk, as if he's in a parade. In another early scene we see him baptized in a lake during a Mennonite service. When he comes out of the water, he giggles maniacally. There's something wrong with the guy.

Small Town Murder Songs shows all of its characters in sharp, detailed poses; they seem the way people do in real life - clumsy, loud, a trifle ugly and knotty. Stormare, who first gained notice 20 years ago in Fargo for putting Steve Buscemi in a wood chipper, plays Walter as a man boiling from within.

Walter is different from most movie cops. He's good at his job, for one thing. He can approach a snarling dog and soothe it. He can walk comfortably into a local strip club to ask questions. He's flawed, with a temper so hot that he's alienated his own relatives, but he's the cop you'd want on your side.

The small town, and Walter's life, is jolted when the body of a young woman is found in some brush near a lake. It's the same lake where Walter was baptized; when an investigator asks Walter if he's familiar with the lake, Walter says, "I was practically born in it." It's the first murder the town has ever hosted, so to speak, and Walter has to work with some special agents to solve it. There's reason to believe the killer was a local dirtbag named Steve. As played by Eric McIntyre, Steve is dirty and rude and is usually seen getting drunk at a karoake bar on the outskirts of town; it's not a stretch to think of him as the murderer.

There's a tangle, though. Walter's ex girlfriend Rita is now with Steve. Why she went from the violent police chief to this Charles Manson-looking geek doesn't say much for her, though it's a small rural town and I guess men are scarce. As more suspicion surrounds Steve, Rita covers for him. Meanwhile, Walter knows something is askew. He'd like to take Steve into the woods and beat a confession out of him, but he can't. He's trying to leave his head-busting ways behind him.

Walter grits his teeth and finds some solace in his new girlfriend (Martha Plimpton), a down to earth waitress named Sam. We're glad Walter has Sam for company, but we're not sure that their quiet dinners together will be enough to quell the inferno inside him.

Writer-director Ed Gass-Donnelly won a slew of awards on the festival circuit when this film was first shown in 2010. He deserved them. He followed it up with a forgettable horror movie - The Last Exorcist II - but he seemed inspired during Small Town Murder Songs. It has the existential ennui of early Terrence Malick. There's no cuteness or glibness in this story about a man trying to redeem himself.

Consider a sequence where Walter is berated by one of his superiors after botching the investigation. We half expect Walter to lose his temper, or to tell the boss to go to hell. But that's because we've seen too many Dirty Harry movies. Walter just sits there and takes it. That's how it would be in real life.

There's a great interest in detail here, from the lacquered green fingernails of the corpse, to the way the town's old-timers speak to each other in Swiss or German. I especially liked a scene where Sam wants to call a woman a whore but spells the word rather than say it aloud; and she misspells it. Glass-Donnelly knew he wasn't aiming for the shopping mall audience, so he could take his time and focus on small things. There's a stomping music score that sounds like Tom Waits in his 1990s, banging on the water pipes period, and loud chapter headings like "God meets you where you're at," but it's the quiet scenes that stay with you.

Still, Stormare carries the day as Walter. It's a role that might've been played in the past by Robert Duvall or Gene Hackman, and Stormare nails it. Long after I've forgotten what this movie was about, I'll remember Stormare's performance.

Small Town Murder Songs is a lesson in how a complex character can elevate a so-so story into something memorable, especially when played by a quality actor.

Friday, March 24, 2017

Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child

It's a striking way to begin a documentary, as we hear the stuttering blasts of Dizzy Gillespie's "Salt Peanuts," while Jean-Michel Basquiat bustles around in his art studio, circa mid '80s, his hair sticking out like it's reaching for the sky. There's a quickness to the cutting, as if we're inside Basquiat's manic head, but the focus - like just about every shot in Tamra Davis' Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child - is on Basquiat's face, rather than his art.

He had the looks of a lazy, spoiled, pretty boy - sleepy eyes, slight androgyny, a style that was pure '80s Manhattan - which didn't quite sync in with his paintings, which were primitive, jagged, tied together with themes of social unrest. What Gillespie has to do with it isn't revealed until much later in the film, when Basquiat talks about his admiration of bebop horn players - and we're supposed to buy Basquiat as having the same fiery brilliance of a Gillespie or a Miles Davis, even though his looks owe more to Culture Club than any act recorded on the old Verve label.

Davis' documentary is a jumpy, colorful, heartfelt look at a neo-expressionistic painter, a haunted example of the '80s New York art boom where approximately 500 hipsters seemed to ignite all at once, creating a lot of bands, a lot of singers, a lot of filmmakers. Basquiat was probably the most revered of the tribe - unless you want to count Madonna, and I don't - but it's faint praise. Sure, there were some great parties going on, but how much of that period is really worth enshrining or discussing?

In his early 20s when the art world beamed its fickle spotlight on him, Basquiat had the kind of slick and sleazy look that was popular at the time. He was dead cool on the dance floor, had played in a noise band called Gray, and was already well-known for being a graffiti artist. As his star climbed, he was befriended by Andy Warhol, who may have seen in the younger man a kindred spirit; Basquiat possessed some of Warhol's ability to provoke and titillate. During the busy years before Basquiat died as a 27-year-old junkie, he appeared to have everything an artist of the '80s could want. It's easy to imagine him branching out into film, or hip-hop; at the least, he might've appeared in underwear ads.

Former girlfriends, gallery owners, art lovers, and associates talk about him the way people in documentaries talk about eccentric geniuses and dead rock stars. They talk about his weird charisma, and the way he hustled, always positioning himself to be in the right place at the right time. He'd lived on the streets for a while, subsisting on Cheez Doodles and the generosity of gullible females.

There are clips of Basquiat being interviewed by Davis, too. He reminds me a bit of another radiant child who died at 27, Jimi Hendrix. Just as Hendrix did on the old Dick Cavett show, Basquiat stares downwards, smiling sheepishly; he's not shy, just unsure of how to deal with the squares who have suddenly noticed him. He certainly won't give up his trade secrets. He doesn't even want to admit that he reads William Burroughs, because he's afraid it will make him sound young.

Pablo Picasso was once asked to describe his greatest talent. His answer was something along the lines of knowing how to make rich people feel important. Basquiat might've said the same thing if he'd lived long enough. His style, which was both childlike and explosive, seemed to grab the attention of wealthy white art collectors who, on some level, liked that they were buying art from a young man of mixed Puerto Rican and Haitian blood who had been a sort of street urchin. He grew tired of being called primitive, but admitted that he liked being thought of as "a bad boy." He knew this played on people's fantasies about artists. He found heroin, however, and as the movie rolls along we see his skin turning splotchy, the paintings slapdash.

What should have been a collaboration for the ages ended in disaster when he teamed with Warhol in 1984. They worked together on several canvases, only to have Warhol dismissed as a has-been trying to get the rub from a younger artist, while Basquiat was accused of being an ego-driven opportunist. And just like that, New York's wunderkind was yesterday's fish.

Basquiat's toothy monsters and graffiti look like the art created in mental asylums - indeed, his mother was institutionalized when Basquiat was a boy - or by first graders asked to draw their nightmares. One can see in Basquiat's paintings a smattering of cubism, and of the African American collage artist Romare Bearden. Basquiat's canvases are like cave paintings, if your cave was in Times Square during the Reagan era. I like his work, but unlike his devoted supporters, I'm not sure he's one of the greats. He died young, which gives his art the patina of importance it might not have otherwise. As for Davis' movie, it feels like a fever dream, with Basquiat serving as a kind of mystical hobo. His sly grin gives him away, though. The rich suckers fall for his every scribble, and he's delighted.

Tuesday, March 21, 2017

POLYTECHNIQUE

Polytechnique (2009) is one of those movies that wallows in violence, but wants us to appreciate the artiness of it all.

There's a major mass shooting every so often - they seem to be yearly happenings now - and there's usually a movie or a documentary to follow. Some are good; some merely exploit sad events. Some, like this one, spread the blood around like Jackson Pollock dripping paint on a canvas.

The problem with these movies is the same one that happens in anti-war films. In order to have something to react against, you must show the violence. And violence, in war movies and in stories about mass shooters, is compelling. It's no surprise that the earliest movies made by Thomas Edison featured boxing; violence captivates a viewer, and taps into our basic predatory instincts. We're supposed to be rooting against the very thing that is enticing us.

That the murders are being exploited is not the real issue, though. The problem is the movie's lofty tone.

A young man with a vendetta against women strolled through a school in Montreal in 1989, armed with a rifle and shooting at "the feminists who have ruined my life." We learn about his hatred of feminists from a hastily written note he composes at the movie's start. We know nothing else about him; we see him staring out the window of his small apartment in a daze; he washes the breakfast plates and then writes his note. Off he goes to his killing spree, and damned if the movie doesn't perk up like a race horse. He scowls, he reloads, he shoots; the halls of the school are soon awash in the blood of feminists.

The plight of the poor women being shot at by a testosterone charged bogeyman is supposed to move us to tears. It almost does, except the director keeps butting in. There's a ridiculous moment where, in the middle of the chaos, the camera stops on a poster of Pablo Picasso's Guernica - a lead-footed attempt to compare the murder of the women to a sort of civil war. The female students, of course, are shown as sweet, hardworking, brilliant young things of lamb-like delicacy. When not studying, they shave their legs for job interviews, only to have their aspirations frowned upon by unattractive middle-aged geezers. At least the women have names. The shooter isn't identified in the movie's credits; he's just "the killer."

The man wasn't born hating women. What happened to him? The director doesn't care; he wants only to show us something terrible. The shooter's name in real life was Marc Lepine; he killed 14 women and wounded many more before killing himself. The movie depicts some of the actual events that came to be known as the "Montreal Massacre," but also throws in some fictional characters. It's nearly as deadpan as Gus Van Sant's Elephant, which was about the Columbine shootings, but there's an underlying theme in Polytechnique that is a bit of a turn off. Namely, that the real tragedy is that the victims weren't merely housewives or store clerks, but were, in fact, educated young women going for their engineering degrees. I'm not certain that an educated person's life is more valuable than, say, someone who doesn't want to design airplanes.

If Polytechinque is too self-important to be a first rate movie, it does have some merits. It's filmed in a murky black and white, and the brewing snowstorm outside gives the school a melancholy, snow globe effect; when frightened students escape out the windows into the snowy dark, they seem to disappear, as if the usually safe confines of the school protected them from nebulous dangers outside. Director Denis Villeneuve surprises us with some Tarantino-esque time play, moving back and forth between events, and Maxim Gaudette is properly grim as the shooter. Karine Vanasse does her best with the heavy-handed role of Val, a survivor of the attack.

On the whole, though, there's something preachy going on. Val has a line near the end when she says, "If I have a son, I will teach him to love. If I have a daughter, I will teach her that the world is hers." This sort of fluff seems scraped from the Oprah channel, or pinched from a pregnant woman's Facebook page.

That leaves the question about exploitation, I guess. One of the first mass shooters, Charles Whitman, who shot and killed 14 people from a tower at the University of Texas in 1966, was portrayed in a movie just a few years later by Kurt Russell. Mass shooters have remained a favorite subject of filmmakers ever since then, and the movies always include dour announcements at the beginning or ending about how this sort of savagery has to end. Of course, in between these announcements, we get 90 minutes of movie mayhem.

The same thing goes on here. The shooter picks off victims, and they drop in ways both artful and horrifying. Because the movie is in black and white, the blood spreads on the floor and the walls like a black oil slick. At the end, the closing credits include the names of the women killed in the actual Montreal shooting. But rather than feel sad, I was struck by how the names looked like a list of bestselling authors, or the high scorers in an old game of Donkey Kong.

Sunday, March 19, 2017

COMPUTER CHESS

I've never been anything but indifferent to computers. As for new streaming services where we can watch movies and listen to music, well, I still find myself struggling with internet connections, and any number of imperfections. I don't feel we've advanced that much since the days when my father would smack the side of our old Zenith television to fix the vertical hold, or when we'd wrap the antenna in tin foil to improve reception.

But there's a loud majority out there convinced that the invention of the computer is the most important thing since the invention of language. Sorry if I don't buy into it.

My grousing is prompted by a 2013 film that was a minor smash on the festival circuit and is now available on Fandor, an excellent movie streaming platform that only shits the bed once in a while. The title, simple enough, is Computer Chess, and in its best moments it is about the weirdness felt by those early programmers who were there at the beginning, the paranoia they may have felt, the loneliness they experienced late at night when the rest of the world was dancing and partying, while they stared into screens trying to solve problems of artificial intelligence, among the most pressing being the question of whether a computer could beat a human at chess.

It takes place at a convention for such would be adventurers - a host actually uses the term "adventure," and that seems apt for these types of people, who don't look as if they've ever journeyed beyond their zip code - where rivals compete to see who has designed the best chess program.

We get the usual types - the greasy haired nerd, the chubby guy wearing a shirt that doesn't fit, the cryptic loner, the angry dude who is too smart for the room, the one female who has an interest in computers, the British guy, and a potpourri of middle-aged professors who moan on and on about "their work," and how much they sacrifice.

Writer-director Andrew Bujalski took a lot of care with casting; he finds a lot of regular looking people, pear-shaped and spotty complexioned, and he dresses them in ways that remind us of old high school yearbooks, or photo albums from the 1970s. He takes the same care with the computers in the movie, big, honking desk models with the glowing screens. Some are so big they need two people to move them. Shot on black and white videotape, it's a great movie to look at; it looks, at times, like a documentary, and you won't be blamed if it takes you several minutes to realize it's not one.

Unfortunately, the movie doesn't want to take any great leaps. It sets up what could be an awesome and rarely tapped premise - the early days of computer programing - but instead settles for some cheap, and not very funny jokes. Apparently, the hotel hosting the computer chess tournament is also hosting a gathering of swingers, and a hippie-dippy self-help group. It doesn't take long for the computer nerds to start mingling with the swingers and the self-helpers, with predictable results.

And after a while, we can't tell one nerd from another; they all look the same.

If this sounds like a knock, it is. But the movie is watchable even when it loses its pulse. It has a fleeting resemblance to early Jim Jarmusch, and even a couple of flourishes that are downright Godard-like.

There are multiple stories going on at the hotel. There's an angry fellow who can't seem to get a reservation, and he wanders around in a state of mild rage until he finally winds up with the self-help group, reenacting his birth. There's a kid who thinks the computers actually take pleasure in competing against humans, and an older professor who tells a story of a computer that made him question the very existence of his soul.

Bujalski weaves the episodes together nicely, but if some of the movie hearkens back to Jarmusch's minimalism, some of it also feels like Westworld. The mix of tones isn't a complete success.

To his credit, Bujalski doesn't play up the obvious discomfort of the one woman in the computer group, and he doesn't turn her into a feminist powerhouse. She does, though, have a compelling scene where she imagines the people at the hotel all seem to be moving like chess pieces.

In a way, the movie reminded me of certain Robert Altman films where a crowd gathers for a concert, or a wedding; they interact, learn nothing, and move on. And we can almost imagine what Altman could've done with this, using actors like Bud Cort and Donald Sutherland as the hotshot computer techies. We know Altman would've focused on the human aspect. By moving away from the humanity of the characters and trying to make things weird, Bujalski just muddles it.

Worse, the characters are perfectly dressed, but not especially memorable. At the end of the weekend, when awards are being passed out, it means nothing because we don't know what these people were really all about, and we couldn't care less who wins or loses.

"Take something mediocre and turbocharge it," says one character, complaining abut the shoddy convention. This movie, though probably deserving of the many festival accolades it received a few years back, could've used some turbocharging.

Saturday, March 18, 2017

ED WOOD'S LOST LOVE: FINAL CURTAIN

Ed Wood Jr. directed Final Curtain as a pilot for a proposed television series to be called Portraits in Terror. In it, an apparently disturbed actor recounts the strange happenings in what appears to be a haunted theater.

The pilot was thought to be lost for decades and maintained a fascination for Wood's cult of admirers. What sort of television show, they wondered, would come from the director of Plan 9 From Outer Space?

Made in 1957, Final Curtain wouldn't resurface until a copy was found by the great-nephew of Paul Marco, an actor in the Ed Wood stock company. It was given a premiere of sorts at the Slamdance Festival in 2012, and has since faded back into oblivion. Still, there's much about it to be admired. It's not the oddball curio for which Wood's fans may have hoped, but it shows a different side of Wood. The pilot also has a lot of folklore behind it, which may have superseded its arrival.

Wood had written the script as a possible vehicle for his friend Bela Lugosi. According to legend, it was the script Lugosi was reading when he died. The irony was tasty for fans of the Wood/Lugosi team, and for all we know, it's a true story. If it's not true, it should be.

According to Wood biographer Rudolph Grey, Final Curtain was one of Wood's favorite projects. Grey doesn't provide any specific incident where Wood said as much, but if there's reason to believe Wood was fond of this pilot, it probably had to do with the subject of haunted theaters. As Wood's third wife Cathy said in Grey's Nightmare of Ecstasy:

"He told me he went to Northwestern University (in Chicago) after he got out of the Marine Corps. I'm pretty sure he took up acting, and I think writing. And that's when he told me he lived in an abandoned theater, or a theater that was dark most of the time, and that's where he got the inspiration for Final Curtain. He felt the vibes, as we say."

The story, what there is of it, concerns an

actor wandering around in the theater where his show has closed. We hear his

thoughts in a voice-over narrative read by Dudley Manlove (known to Wood

fans as Eros in Plan 9 From Outer Space) and it's pure,

over-the-top Wood, with a lot of hokum about "the witching hour," and

and how spirits come out to cavort in the darkness, "to die, and re-die, to

live and relive..."

Eventually the actor (played by Duke Moore, who would appear in several Wood projects) is lured to a storage room where he discovers a strange mannequin in a closet. She comes to life, and beckons him to join her. She's one of Wood's great creations, her long fingernails reminiscent of Vampira's. Say what you will about him, but Wood could create a striking tableau. Tor Johnson coming out of the grave in Plan 9, for example, is comparable to anything from the Poverty Row horrors of Wood's youth; this mannequin, played by Jenny Stevens, is equally unforgettable. Sure, we can see her arm moving slightly, so we know she's a human and not a doll, but she's creepy. The actor flees, and eventually comes to his own morbid end. It's like Tales from the Crypt, without the sexy stuff.

If we need proof of Wood's fondness for this 20-minute episode, consider the ways he recycled it. First, he took the great scene of Jenny Stevens' alluring mannequin and inserted it into one of his next films, Night of the Ghouls (1959). In 1963 Wood was still tinkering with the omnibus idea, proposing a film version of Portraits in Terror that would include Final Curtain along with another of his short films, The Night the Banshee Cried. When Wood wrote the novelization of his own Crypt of the Dead (1965) he incorporated much of the Final Curtain story. In his 1975 paperback collection, Tales for a Sexy Night Vol. 2, he included a prose version of Final Curtain. Finally, some of the verbiage in Final Curtain sounds suspiciously like material from Plan 9. It was undoubtedly a story Wood wanted us to know.

One reason Wood should have been proud of Final Curtain is its look, which is a few shades better than most of Wood's movies. Filmed in an actual theater at Ocean Park Pier in Santa Monica, it doesn't distract you with cheap sets and makeshift scenery. Wood and his longtime cinematographer Bill Thompson (who made his debut in 1914, filming King Baggot in Absinthe) lurk around the theater, filming backstage and along the lonely corridors; they knew where the spooks were hidden. They also get some great shadowy shots of Moore on a spiral staircase, as if Wood had been spending his free time watching Fritz Lang movies.

Looking slightly overstuffed in his tuxedo, Moore is a credible stand-in for Lugosi. Would Lugosi, Wood's original choice, be any better? Perhaps for camp value. Moore, to his credit, takes the role seriously, peering around the corners of the dark theater as if fearing what he might see. By '57, Lugosi was too dissipated; Moore looks robust, and we can believe he was some sort of theatrical idol. With Wood directing him as if he's in a silent movie, Moore is gallant.

Where Wood disconnects from some viewers is that he was irretrievably stuck in the 1930s. The B movies, the Saturday matinee serials, The Mummy and Dracula, the comic books and radio shows he'd loved as a kid, had such a profound impact on Wood that his strongest desire was to recreate them. His detractors like to say that if he'd had bigger budgets, he'd still make a cheap, tasteless product. That may or may not be true. Besides, if you gave Ed Wood a million dollars, he'd probably give most of it to Lugosi, just to keep the old guy out of trouble.

Unfortunately, if you can't get past Wood's penchant for angora sweaters, or the Johnnie Depp movie, or Wood's reputation as the worst director of all time - a title that certainly doesn't fit him considering the dross that plays in our cinemas and on cable every week - you're missing out on the work of an idiosyncratic artist who, against odds that would cripple most of us, practically willed his ideas into existence. Worst of all time? Sometimes I think Ed Wood is nothing less than a hero.

Watch Final Curtain on The Film Detective's classic movie app, available on Roku, Apple TV, and Amazon Fire TV.

Thursday, March 16, 2017

BOOKS: A STRAY CAT STRUTS

JUST A KID FROM MASSAPEQUA WITH A MODEL AT HIS SIDE

Slim Jim Phantom and his Quest for Cool

by Don Stradley

The

Stray Cats were one of the stranger pop culture stories to come out of

the early 1980s. Three young guys from Long Island, dressed up as

rockabilly dudes, ripping it up alongside The Clash and Duran Duran. It

made no sense then, and after reading Slim Jim Phantom's quaint A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel,

I'm still not sure how to explain it. Of course, the Cats were a fine

band and they fired off a handful of memorable tunes, and Brian Setzer's guitar licks were supple and bright, and the band's image was indelible, and one

of my favorite CDs is a live set they recorded in 2004 called Rumble in Brixton;

but since when does talent get anyone to the top? I'll always think of

the Stray Cats as an anomaly, an accident, something that slipped

through the cracks, like an alley cat that sneaked into a restaurant and

ended up being the chef's favorite. What lesson can we learn from the

Stray Cats? That hard work and chutzpah is rewarded? That enthusiasm

pays off? Like the Bermuda Triangle and the pyramids at Giza, the Cats'

success mystifies. We didn't know we needed them until we saw them.

The

Stray Cats were one of the stranger pop culture stories to come out of

the early 1980s. Three young guys from Long Island, dressed up as

rockabilly dudes, ripping it up alongside The Clash and Duran Duran. It

made no sense then, and after reading Slim Jim Phantom's quaint A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel,

I'm still not sure how to explain it. Of course, the Cats were a fine

band and they fired off a handful of memorable tunes, and Brian Setzer's guitar licks were supple and bright, and the band's image was indelible, and one

of my favorite CDs is a live set they recorded in 2004 called Rumble in Brixton;

but since when does talent get anyone to the top? I'll always think of

the Stray Cats as an anomaly, an accident, something that slipped

through the cracks, like an alley cat that sneaked into a restaurant and

ended up being the chef's favorite. What lesson can we learn from the

Stray Cats? That hard work and chutzpah is rewarded? That enthusiasm

pays off? Like the Bermuda Triangle and the pyramids at Giza, the Cats'

success mystifies. We didn't know we needed them until we saw them.Barely out of the litter box, the band became a favorite mascot of the Rolling Stones, all fans of the 1950s rock 'n roll style being aped by these Long Island boys. Phantom, who wrote the book without help from a ghost writer (which deserves kudos, because I'm sick of barely literate slobs hiring pros to make them sound like Hunter S. Thompson) describes his early encounters with Mick Jagger in the way you'd expect from a New York kid. "The whole scene was a kind of summoning to a mythic figure," he writes about a visit to Jagger's office. "He was holding an antique hand mirror with a big pile of coke on it." The style never veers; it's endless awe and gratitude for the situation that has dropped into Phantom's lap, including friendships with such diverse characters as Lemmy and Harry Dean Stanton, plus a surplus of gorgeous women that us non-rockers never meet. He doesn't kiss and tell; he's actually rather gentlemanly. "We are still together," he says of the current woman in his life, "and she's my girl." Sweet, eh?

There's a smattering of backstage stuff, but it's all rather tame. Jerry Lee Lewis comes off as eccentric; Keith Richards as earthy; George Harrison as eccentric and earthy; Johnny Ramone as a bit of a control freak; Setzer as egocentric; none of it makes for a galvanizing memoir. Phantom falls too easily into the "Aw shucks, I'm just a drummer," role, but once in a while he cuts loose with something that penetrates, like his observation that "the cast of the Grand Old Opry had as much sex, drugs, and rock and roll as Led Zeppelin, the main difference being the volume of the drums on the records." Or when Lemmy offers him a special concoction off the blade of a buck knife: "It felt like someone had shot an orange flavored metal arrow up my nose and through the top of my head. I was frozen. I couldn't talk. I couldn't even blink." And like all rockers of a certain age, Phantom offers tributes to his dead pals, and a sense of Gee, how lucky am I to still be here?!

Phantom refrains from anything that might counter his nice guy image, to the point where we wonder if he's holding back. He certainly doesn't say much about the Stray Cats. Their early days were a whirl of kismet, and he's still flabbergasted by how hugely famous they were for a while, but he offers little about on his band mates, except to say the trio simply grew apart in the way successful bands often do. Early on he describes a chat with Stones bassist Bill Wyman, who wasn't especially forthcoming with info on Mick or Keith. "I myself have been in that conversation a thousand times," Phantom writes, "being on the receiving end of the 'What's your lead singer really like?' question." From that, we can gather, Phantom will take Wyman's tip and not divulge much regarding the Cats. We'll learn about his first wife Britt Ekland being a sweetheart, and John Candy stumbling drunk outside an L.A. club, and the trials of running the Cat Club on Sunset Boulevard, and Phantom falling from a stage and breaking his arm, but it's all just enough to keep the line moving, like he's entertaining fans with quick stories at an autograph signing. What he's learned over the years is how to keep us at a safe distance, to give us enough tidbits to make us forget we're outsiders.

Sunday, March 12, 2017

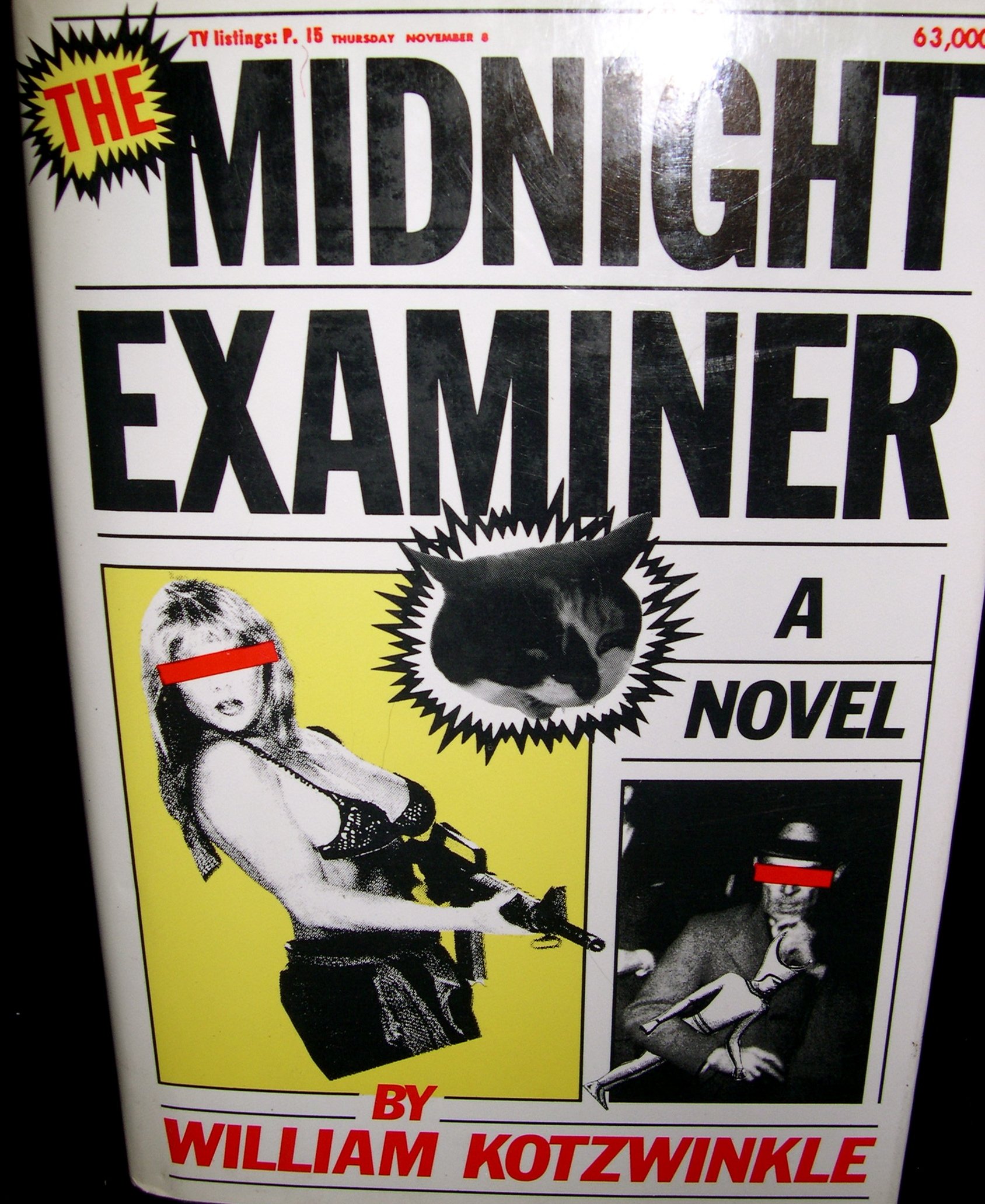

BOOKS: THE MIDNIGHT EXAMINER

HOW BELLY DANCING SAVED MY MARRIAGE

I find the darnedest things at my local swap shop

by Don Stradley

William Kotzwinkle is one of those writers - as quaint and precious as a scented candle, a name that meant a lot to college kids during the 1970s and '80s, a kind of less threatening Kurt Vonnegut, utterly convinced that satire was some kind of thorny cudgel - that I never quite got. He's in good company, because I never got Saul Bellow or Theodore Dreiser, either. I once crapped out in the middle of a John Le Carre novel because there were too many characters in it. Yet, I was always touched by the people who loved Kotzwinkle. He was their dry-witted avenger, their cuddly, slightly skewed hippie uncle figure who won awards and, shock of all shocks, was hired to write the novelization of ET, The Extraterrestrial, which for a writer whose name rhymed with "twinkle," as in "Twinkle twinkle little star," seemed beautifully appropriate. I recently found a copy of The Midnight Examiner, Kotzwinkle's 1989 send up of the supermarket tabloid industry, and though I still don't quite get him, I like him a bit more. Like the neighbor who annoys you with his opera music, he's not so bad if you get to know him.

It takes no time at all for us to understand the lightly cynical world of The Midnight Examiner. The worn out hacks at Chameleon Publications, a New York group responsible for a line of magazines with names like Macho Man and Knockers, churn out stories about plastic surgery gone awry, dead people being eaten by their cats, and my favorite, a little girl who has a UFO stuck in her uterus. The staff dreams of L.A., where "the face lift hospitals have valet parking," but despite assembling portfolios for more highbrow magazines, they know they're not getting out of their world of alien hookers. The style here is newsroom farce, His Girl Friday if Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell were bitter, hopeless alcoholics, with Kotzwinkle spinning out the dialogue as if he'd just seen a late night showing of Room Service, or worse, an episode of M.A.S.H. where Alan Alda does his Groucho act. The hybrid of newsroom razzle with tabloid schlock must've been tempting, but wading through it becomes a chore.

There's also a funny bit where a story about an exploding vibrator is squashed because one of Chameleon's chief advertisers is a company that manufactures vibrators. And there's a guy who gets a job as an editor based on his once writing a series of prank letters to the Village Voice. There's an inspired moment where a writer talks proudly about meeting a reader who truly loves the stories from Chameleon Publications, describing them as something like aspirin. When a co-worker questions if so many aspirins are good for a person, the writer responds, "If you've got a headache that won't quit, they are." And of course, the senior members of the staff fear aging. "I'm never going to look at my old movie magazines again," says one. "It's a shock to the system, seeing June Allyson as a young girl." But Kotzwinkle is actually better when he puts his humor aside and focuses on the story's underlying theme: the vanishing of New York.

The Manhattan of the 1980s was an unpleasant place, and The Midnight Examiner is bursting with mobsters, crackheads, voodoo queens, and delusional war veterans. Still, the memory of better days days lingered. "If you turn and look back in the twilit hour," Kotzwinkle writes, "you can see the old ghosts of Manhattan pulling up in their horse drawn carriages." Nowadays, I suppose you have to grind your way through the annoying tourists, with hopes of seeing the ghosts of old crackheads. Ultimately, Kotzwinkle has little to say about the milieu of cheapo magazines and the people who make them. Now and then, though, he hits a perfect note, like when the staff goes to lunch in Chinatown. "We turned on Twenty eighth, past windows full of jade turtles, ivory unicorns, and turquoise horses whose bridles sparkled with little gem stones. Fate had cut us off from the prestige and perks of the regular corporate world, but as a kind of compensation we, like these supernatural creatures, lived in an arcade of dreams, turning out fairy tales for the modern reader." This says more than Kotzwinkle's tired slapstick, as does a character quietly grousing that Chameleon magazines are never in the reception area of his psychiatrist's office.

Saturday, March 4, 2017

BOOKS: LONELY BOY - Tales from a Sex Pistol...

SEX AND DYSFUNCTION AND ROCK 'N ROLL

A punk rocker tells his tale

By Don Stradley

I

always figured the Sex Pistols could've made it in America based solely on Steve

Jones' guitar. John Lydon's caterwauling vocals and Sid Vicious' goofy presence

aside, it was Jones who might crack through America's thick, clannish wall. No

one in the U.S. would care much about the band's

reputation in England - we don't

really get the whole business with the queen and the royals, and the

whole punk

fashion thing seemed silly to most of us who were still listening to Frampton, or our older brother's Zappa albums - but Jones' guitar

could grab anybody by the ear. Though he was once planted at #99 on

Rolling

Stone's list of the top 100 rock guitar players of all time, he remains a

largely unappreciated musician. I loved his style - it was raw, but

smart - and

his best riffs on Never Mind The Bollocks… have the feel of a man

escaping down a clear road on a motorcycle, making hairpin turns and nearly

cracking up. Listen to the crashing chord that introduces "Holidays in the

Sun." A hundred guitarists using the same equipment in the same studio could hit the same

chord, but none would sound like Jones. His way sounded like a call to arms, a

warning shot announcing a street rumble where bones would be broken and

souls trampled under jackboots.

I

always figured the Sex Pistols could've made it in America based solely on Steve

Jones' guitar. John Lydon's caterwauling vocals and Sid Vicious' goofy presence

aside, it was Jones who might crack through America's thick, clannish wall. No

one in the U.S. would care much about the band's

reputation in England - we don't

really get the whole business with the queen and the royals, and the

whole punk

fashion thing seemed silly to most of us who were still listening to Frampton, or our older brother's Zappa albums - but Jones' guitar

could grab anybody by the ear. Though he was once planted at #99 on

Rolling

Stone's list of the top 100 rock guitar players of all time, he remains a

largely unappreciated musician. I loved his style - it was raw, but

smart - and

his best riffs on Never Mind The Bollocks… have the feel of a man

escaping down a clear road on a motorcycle, making hairpin turns and nearly

cracking up. Listen to the crashing chord that introduces "Holidays in the

Sun." A hundred guitarists using the same equipment in the same studio could hit the same

chord, but none would sound like Jones. His way sounded like a call to arms, a

warning shot announcing a street rumble where bones would be broken and

souls trampled under jackboots.Aside from his occasional reunions with the Sex Pistols, Jones has seemed content to forget those old riffs in favor of a variety of sounds, working with his own bands like The Professionals and Chequered Past, and serving as a gun for hire for everyone from Siousxie and the Banshees to Iggy Pop. For a while Jones wore his hair like Fabio and seemed to be deliberately removing himself from the Sex Pistols legacy. Still, when the band reunited in 1996 and sporadically during the 2000s, it was Jones' guitar that brought back the old chills. Are there really 98 guitar players better than Jones? There may be some technical wizards out there, some with a greater library of classic riffs, but I'll be damned if there are 98 who can make the hair on my neck stand up the way it does when I hear Jones, especially if I haven't heard him for a while.

There's always talk that The Sex Pistols could've been enormously successful had they stayed together beyond one album and one half-assed tour of America, that the success that came to U2 or The Police could've been theirs, but this isn't necessarily so. They were probably too abrasive for America, too strange, too unwilling to play the game. Plus, Jones didn't much care for Lydon's company. And if they'd managed to stay together and get rich, a heavy drug user like Jones might've followed Vicious into an early grave. Though kismet seemed to put them together - all were young guys hanging out at Malcolm McLaren's clothing shop when he was thinking about managing a rock group - you can't say luck was ever on their side. On their last tour in 2008, they came to the end without a profit, thanks to the economic crash. Lucky for Jones he's been able to pay the bills courtesy of his popular L.A. radio show, Jonesy's Jukebox. That particular job has kept him out of trouble for years. He interviews his friends, brings on musicians he admires, plays his favorite songs, and plays his guitar a bit, too. It was an unlikely, but safe, place for him to land.

These days he meditates. He took spin classes until he hurt his back. He makes amusing cameo appearances on shows like Portlandia - there he was on Craig Ferguson's farewell show, too, playing his scratchy power chords as Ferguson bellowed the lyrics of "Keep Banging On Your Drum" - but what's most interesting, along with the fact hat he can still play that damned guitar, is the way he looks now. He used to be such a boyish little guy - McLaren had originally thought of calling the band "Kutie Jones and his Sex Pistols," as if Jones was going to be the Shaun Cassidy of punk - but these days Jones is carrying some extra weight and looks like he could be a hitman in an old Michael Caine movie. No one would've guessed that this was what punk would look like in middle age. Then again, Jones is the first to tell you that he wasn't a punk, that he'd never really dressed the part and didn't have the hair for it. He's always been on his own, unpredictable path. To quote Chrissie Hynde, "no one could've predicted Jonesy."

Nor could anyone predict that his new memoir, Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol (Da Capo Press), would be such a frank confessional. Jones' book, which has its share of humor and rock 'n' roll moments, is a surprisingly insightful record of what can happen to a boy when he's victimized by sexual predators, as Jones was as a kid.

Throughout the memoir, Jones refers to himself as "damaged goods." At various times he's been an alcoholic, a junkie, a peeping Tom, a sex addict; he can't have normal relationships with women. Sex, which he begrudgingly accepts was one of his many addictions - though anyone reading the book could see it was obviously so - was just a distraction from his inner turmoil. He was a screwed up adult, and it's not surprising. He experienced some childhood incidents that would leave most people fairly well-scarred.

For a barely educated bloke, he's actually quite good at examining his behavior, especially his years as a kleptomaniac. There was nothing Jones wouldn't steal. Hell, he once stole a coat from Ron Wood, a guitar tuner from Roxy Music, and some sound equipment from David Bowie, including a microphone “that still had a smudge of Bowie’s lipstick on it.” The sense of excitement thrilled him, especially when his thefts made the news. In a rather brilliant aside, he says his thieving days help him understand mass murderers and arsonists.

“It’s that level of narcissism where you get excited because you’ve made your mark on the world and no one knows it’s you,” he says. “You’re so alienated from humanity that you don’t care how much damage you have to do to get that feeling.”

By turns cynical and self-deprecating, blunt and wickedly funny, Jones keeps the tale moving briskly. He tells it as he remembers it. Granted, he doesn’t always remember things vividly – he was too busy shagging birds in an alley while high on one drug or another – but since he was always the mystery man of the Sex Pistols, any small detail feels like a gold nugget. He admits to asking his friend and former Pistol Paul Cook for help with some of the blind spots in his memory, but he doesn’t seem too hell-bent on accuracy. He addresses a few misconceptions, and actually does a lot to restore the reputation of McLaren, long thought to be the devil incarnate who ruined the Pistols, and unleashes some telling snapshots of his old band mate, Lydon.

But Lonely Boy, written with an assist from Ben Thompson, is less a showbiz memoir than the story of a troubled man who happened to move in showbiz circles. It’s like a session of binge drinking with a jolly old uncle who tells a lot of risqué stories, and then shocks you with some intimate bits that you hadn’t expected to hear. Ultimately, it’s a moving story, told with as much candor as we can expect from a man who has spent a career relinquishing the spotlight to others.

Die-hard Pistols fans, however, will relish the discussions of Sid Vicious joining the band, and Lydon’s bizarre audition, and how the Pistols' sound was born. They may be shocked when Jones says he wishes he’d been in The Clash, or that he was secretly a fan of bands like Boston and Journey. But the story will be of interest even if you’ve never heard a single note of the Sex Pistols. It’s that well told.

If Jones’ guitar playing was deceptively complex, so is his style of storytelling. He sounds like he’s being matter of fact and humorous about everything, but there’s always a pinch of estrangement in each chapter. His joking manner is a kind of shorthand, but Jones, now 61, is still harboring hurts and insecurities.

He learned the guitar on his own, holed up in his childhood home in West London, scarfing pills to help his focus. It was a nice break from the perverts who stalked him under bridges, and the general sense of decay and corruption that made up the background of his life. “There were building sites and debris everywhere,” he writes. “It was like the whole place was falling down around us.” But he credits his atrocious childhood with the advent of the Pistols, adding, “It was my shit upbringing that got the ball rolling. That’s not me showing off, it’s just a fact.”

In this book we see Jones revealing different facets of his being. There’s the kid who loved nice clothes and shoes, the terrible student, the petty thief. He refers to himself at various times as a phantom, a werewolf, a daring burglar with a cloak of invisibility, and compares himself more than once to Alex of A Clockwork Orange. (Jones uses so much Brit slang in the book that you may think you're reading A Clockwork Orange!) Most winning of all, though, is the thieving kid who found unexpected comfort in music, loving everything from Rod Stewart to Jimi Hendrix, to Elvis, to prog rock. Hearing “Purple Haze” coming from a neighbor’s window was a special moment:

“There was a catchiness about it as well as the power, and I loved the syncopation, the way Hendrix’ guitar would kind of go ‘clunk’ and then ‘weeeoh!’”

And then later, the boy who never really had a proper mentor finds one in the most unlikely of people: Malcolm McLaren.

"He had his fucking issues, same as we all do, but I couldn't help but like him, and I got a lot out of our friendship - probably more than he knew."

Jones tells the story of the Sex Pistols and their crazy ride to fame like he’s describing a party gone dangerously out of control. It started out in a fun way, with him nicking equipment so the unpolished players would at least look professional, and the time spent songwriting and in the studio yielded magnificent results, even though the negative quickly outweighed the good: the absurdity of the U.K. media circus; the attacks in the street on Cook and Lydon; the rise and fall of Vicious; the phenomenon of fans spitting and hurling beer bottles.

Of the insidious presence of heroin in his life, Jones recalls that he never felt like he was the worst of junkies, though he once overdosed in a toilet stall at a sushi restaurant. He never took part in “shooting galleries,” which struck him as unclean. He was always sure to bring his own syringe, though he describes this as akin to bringing his own cue to a snooker hall. He maintains that he was an alcoholic who merely stumbled into heroin use. His addictive personality had a lot of moving parts, and heroin was just one aspect. Wandering through New York’s infamous Alphabet City in the 1980s hoping to score was one of the low points of his drug years. “It was scary, but I knew I had to do it. The thought of getting high was all that was keeping me going…being a junkie felt like a necessity after the Pistols ended.”

If the band had given him a sense of belonging, he never quite became friends with Lydon, AKA Johnny Rotten. Lydon comes off as a whining, immature character surrounded by yes-men. But, Jones reckons, Lydon’s snotty attitude, “was exactly what the Sex Pistols needed.”

He does praise Lydon for his vocals, and he’s particularly fond of Lydon for turning down the Sex Pistols’ induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Still, there is likely to always be friction between them. By the end of the 1996 reunion tour, Jones writes, “we were every bit as fucking sick of each other as we had been when the band first split up.”

Jones is equally direct with his impressions of other people in the music biz, including many that he’s met through his radio show. Brian Wilson, for instance, was “a complete cunt. Just because he’s supposedly a bit nuts, that’s no fucking excuse to not be a nice person.”

In the course of Lonely Boy, Jones discusses his tough years in 12-step programs, his difficulties in taking responsibility for his life, dealing with one of his childhood abusers, a sketchy relationship with his mother, and not learning how to read and write until he was grown. A meeting with his biological father goes reasonably well, but he knows going in that a real relationship with the guy, an ex-boxer named Don Jarvis, isn't likely. He just seems glad to finally meet him and learn he’s not a jerk. Music, though, remains a constant companion, if no one else will.

Jones manages to portray himself as a serious musician, not just a meathead who turned the volume up. There’s even gentleness in the way he discusses the guitar, like it’s a loyal dog he can always count on. Even during his darkest days, he was able to play, and be proud of what he did as a guitarist and a Sex Pistol. He’s never sentimental, though. “The Sex Pistols were born to crash and burn, and that’s exactly what they did.”

Yet, there are clues throughout the book that the band's sudden demise was something from which Jones never quite recovered. Bands are like marriages, and the breakup of a band, especially when it's the first time a guy feels like he's part of something, can be as devastating as any divorce. How can we read Jones' recollection of an early gig at St. Martin’s art college and think otherwise?

“I was thinking, ‘This, right now, is the best thing in the world.’ He (Lydon) was the singer and I loved playing in the band with him and the whole thing felt fucking great. Sadly, that feeling wouldn’t return too many times," Jones says. "But at least I’d always have the memory.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)