Many years ago, at what

was probably the zenith of her career, Grace Jones made an appearance on the

Arsenio Hall show. The other guest was middleweight boxer Thomas

Hearns. Jones was there to promote a movie, perhaps Vamp, or A View to a Kill. Hearns, most likely was promoting a fight.

Late in the show Jones brought her mother out and introduced her to the studio

audience. Hearns, a gentleman, stood up and gave Jones’ mother a warm hug.

Jones complained that she hadn’t received similar treatment. As the audience

roared, Hearns grinned and said, “I got somethin’ for you later, baby.” Jones

bared her large white teeth. She looked

as if she might reach over and devour Hearns whole, stopping only to spit out

the glass jaw.

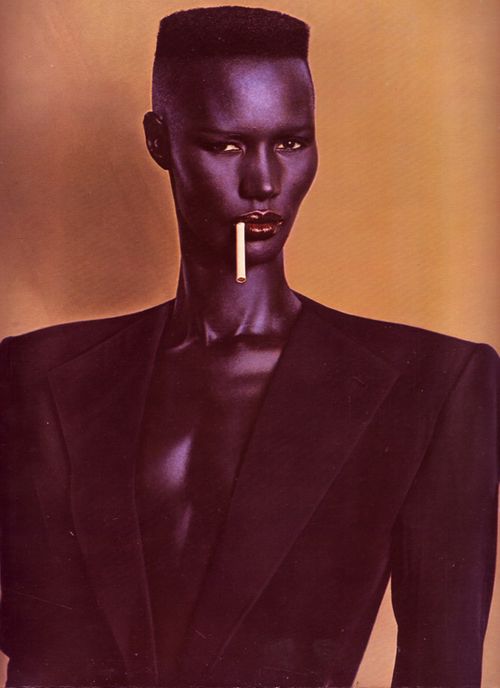

That was

Jones’ image in those days, that of the carnivorous man-killer, stomping her

way from fashion modeling, to singing, to acting, as if her talents were too

large to be contained in a single genre. In films, she’d gone toe-to-toe with

Conan the Barbarian and James Bond. You don’t get to do that that unless your

image reads: Amazonian eater of souls.

The bulk

of her highly readable new book, I’ll Never Write my Memoirs, has

to do with dispelling that image, which she insists isn’t the real Grace, but a

heightened version of herself that is both impossible to categorize and

timeless.

She

writes, “You can find images of me from centuries ago, faces that look like

mine carved in wood from ancient Egypt, Roman times, the Igbo tribe of southern

Nigeria, and sixteenth century Jamaica, fierce enough to turn people pale, to

shrink their hearts.”

Funny,

angry, earnest, and vulnerable, Jones keeps her age a mystery but is

forthcoming about everything else. Writing with surprising ease and beauty, she

tells the tale as she remembers it, sometimes fudging the timeframe because the

year something happens isn’t as important as why or how. She creates a

fascinating trip through four decades of her life and the pop culture, from the

disco era of powder blue Rolls Royces and buckets of cocaine, to the

AIDS-wracked 1980s, to her several brushes with controversy, including a number

of nights spent in dirty jail cells, and the time she roughed up a British TV

host. She also offers candid remarks about various colleagues, saving her most

savage commentary for her longtime partner and hindrance, celebrity itself.

The

book, written with her journalist friend and frequent collaborator Paul Morley, covers more than prickly showbiz

trivia. It’s also a heartfelt recounting

of a black woman trying to define herself in an era where black female

entertainers were supposed to look like Diana Ross and strive for a career in Las

Vegas. It’s an inspiring howl from a human hurricane who shares the secrets of

her hard work and her unique art. And it’s the frequently sad story of a woman

who escaped an oppressive childhood of “serious abuse,” only to find herself

constantly battling more oppression elsewhere. If it seems Jones pauses too

often to congratulate herself on one triumph or another, it’s well-deserved.

When you fight like she did against such incredible odds, it’s reasonable to

step back and marvel at yourself. But then, Grace Jones has always been a

one-woman victory parade.

Hardcore

Jones fans, of course, will scour the pages for the naughty stuff, the sex,

drugs, and scandal, the romance with Dolph Lundgren, for instance, and the

“contagious, transgressive abandon” of disco’s early days. It’s all in there.

But the book will also dazzle those who may think of Jones only as a cartoonish

relic of the Studio 54 era. The book is that captivating, and well-told.

Jones

was always a visual performer, and her storytelling is filled with flourishes

that nearly match the outlandish fashions she’s been known to wear. How much of

this story was shaped by Morley is unknown, but it’s such a joy to read that it

doesn’t matter. The collaboration results in a narrative that is both pointed

and poetic. “Fireflies scatter into the night,” she writes after an outdoor sex

romp, “each with its own incredible story to tell.” It’s as if Jones decided

that even dishing on herself deserved the most thoughtful presentation.

Though

Jones devotes considerable attention to her artistic processes, it seems her

proudest accomplishment was the gradual creation of the “Grace Jones”

character, which she describes as “a little bit of Kabuki stillness, a warrior

slash of drag debauchery, a dash of black humor, shoulders out of a gothic

fantasy, and a load of tease.” Of course, she had help from designers,

photographers, and producers, but the ultimate fruition of her character came

from her own tangled depths. This great alter-ego she wore could only

be hefted by a woman like Jones, “a snake with the upper body strength of a

galley slave.”

In these

21 chapters, we see Jones through every evolution of her being. There’s the

tomboyish girl in Spanish Town, the girl who endured regular whippings by her

sadistic step-grandfather, the girl who seemed suspicious of her very

surroundings, including the giant moths that were allegedly the reincarnated

spirits of ancient ancestors, the feral dogs roaming the streets, and the rough

Rastas lurking “at the edge of vision, as tangible as phantoms…” There’s the

girl who escaped to Philadelphia and became an acid dropping go-go dancer, a

voracious sponge absorbing every experience imaginable.

And

later, the disco queen known for her outrageous costumes and hostile behavior.

“The

craziness was a fire I lit to keep danger at bay,” she writes.

Danger

seemed everywhere, even in the underground clubs where she first became a star,

where “it seemed like there were bodies on bodies, some of them so close they

were penetrating each other, lubricated by their own sweat.” She conveys the

exhausting rigors of performing, the heartbreaking failures at auditions, and

the ongoing frustration at meeting men who’d fallen in love with her image but

seemed less enamored of the real Grace, a woman content to sit at home and

watch tennis on television, or sprawl on

the floor with a 1,000 piece puzzle. Her best relationships seem to have been

with older male mentors, such as Chris Blackwell, the Island Records founder

who was behind some of her best music. Mostly, the men in her life flaked out

on her, grew egotistical. One held knives to her neck and threatened to cut off

her head.

Of the

movie years, when she starred alongside Arnold Schwarzenegger and Roger Moore,

Jones recalls them as a fun time, though the film industry was “a motherfucking

beast.” Casting directors didn’t know how to use her. When the movie roles

dried up, she returned to music. By then, the music business thought of her as

a golden oldie. A contract with Capital turned sour. And just like that, her heyday

was over.

Fame’s

hideous side was always apparent to Jones, and she’s spot on when she describes

the antics at Studio 54 in the 1970s as “a harbinger of the haywire

shamelessness of reality TV – minor celebrities fighting among minor

celebrities to avoid losing their fame, demented role playing, the not so

famous doing whatever it took to get some attention, the truly famous and aloof

and immune watching it all as a kind of sport for their amusement.”

Though

Jones, now a grandmother, remains busy with interesting projects, she’s earned

a steady paycheck in recent years by appearing at corporate events. Apparently

she jumps out of cakes, dressed as a leopard, or something along those lines.

She cracks the bullwhip a few times, sings a couple of the old hits, and calls

it a day. But don’t think of this as a comedown. To appear at these silly

events, she demands to be put up for three days in the presidential suite of a

5-star hotel, and doesn’t perform unless she’s paid in advance. She once

learned that a company had spent more on floral arrangements than they’d

planned to pay her, so you can imagine how that went down. Once, when a group

had failed to come up with her performance fee, a desperate woman offered Jones

a newborn baby to hold as collateral until the money was raised. These

anecdotes show the corporate world to be as silly and grotesque as the

entertainment business.

Jones’

observations of various friends and contemporaries are equally vivid. She

writes that Andy Warhol “surrounded himself with action…as though he was more

active than he actually was.” She describes model Jerry Hall as having “a head

full of blonde hair and a mouth full of Dallas.” As for Lundgren, “People

started to fill head with stuff because they saw a chance of making money with

him, and he believed it.” She describes couples therapy as “satanic nonsense,”

and pans women who undergo cosmetic surgery as “self-hating,” and being part of

a “mass panic.”

In the

course of I’ll Never Write My Memoirs,

Jones also shares a lot about her family, a conservative lot of self-appointed

Pentecostal bishops, in a surrounding of “Bible-black ugliness.” Much of her

scowling stage presence, she reveals, is an aping of her horrific step-grandad.

Yet, two of the book’s most moving chapters involve her return, in her adult

years, to Jamaica, which she grew to appreciate, and a touching tribute to her

father, a bishop who often felt backlash in his community because of Jones’

capers, as if her reputation was spitting out poison that reached all around

the world.

Jones

also worries about current singers, from Lady Gaga to Kanye West. While

acknowledging that many present-day performers have borrowed liberally from

her, she wonders if they have her instincts for survival and reinvention. Her

own story is littered with tales of suicide and accounts of friends who were

mysteriously “swallowed up.” Jones doubts the new generation possesses her own

tough hide, and fears there are many more casualties to come.

One of

this electrifying book’s many strong points is Jones’ ability to describe the

madness that comes with fame, and how it slowly eats one from the ankles up.

Whether you’re being mobbed by admirers, or simply gawked at by a few dozen

devotees in a sweaty club, there’s something categorically ghoulish about it.

The only good thing about being famous, Jones declares, is that you can meet

other famous people and discuss how awful it can be.

“When

you walk through that door, through to other side, where there is fame, you

cannot believe how different it is,” she writes. Fame, she says, “passes

through you as you pass through.”

- Don Stradley