New bio tells the sordid tale of iconic writer...but was he really so great?

by Don Stradley

Iceberg Slim, the former pimp turned author, was troubled by nightmares throughout his life. The one that haunted him most involved a bunch of prostitutes groveling at his feet. With his dagger sharp pimp shoes, he’d start kicking them to death. As they thrashed around on the ground like dying chickens, Jesus would appear and offer Iceberg Slim a whip to finish off the final whore. As Slim lashed away, he realized that the woman was his mother, knee deep in a river of blood. He would always wake up at this point, filled with horror and guilt. Iceberg Slim allegedly harbored profound guilt feelings over his pimping career, especially since his mother was such a religious woman. Conversely, it was his mother’s affair with a lowlife hustler that brought Slim to the conclusion that women were easily manipulated. Yet, Slim loved his mother. This lifelong quandary, and the fact that such well-known black figures as Mike Tyson and Ice-T have praised Slim’s novels, makes him a nice candidate for a detailed biography.

by Don Stradley

Iceberg Slim, the former pimp turned author, was troubled by nightmares throughout his life. The one that haunted him most involved a bunch of prostitutes groveling at his feet. With his dagger sharp pimp shoes, he’d start kicking them to death. As they thrashed around on the ground like dying chickens, Jesus would appear and offer Iceberg Slim a whip to finish off the final whore. As Slim lashed away, he realized that the woman was his mother, knee deep in a river of blood. He would always wake up at this point, filled with horror and guilt. Iceberg Slim allegedly harbored profound guilt feelings over his pimping career, especially since his mother was such a religious woman. Conversely, it was his mother’s affair with a lowlife hustler that brought Slim to the conclusion that women were easily manipulated. Yet, Slim loved his mother. This lifelong quandary, and the fact that such well-known black figures as Mike Tyson and Ice-T have praised Slim’s novels, makes him a nice candidate for a detailed biography.

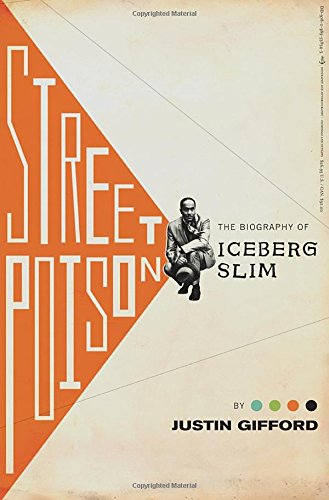

There

are plenty of gruesome details in Justin Gifford’s Street Poison, The

Biography of Iceberg Slim, but for every horrific moment of Slim’s life,

Gifford pauses the action to tell us about the importance of it all, or to

dryly recite a black history lesson, just to show how the mighty Iceberg Slim rose

above the racial climate of the day. A bit of this would go a long way, but

Gifford blurs the line between biographer and cheerleader, dulling some of the

book’s edges. Also, though Gifford tries to separate fact from fiction, he

allows some rather fantastic stories to go unchecked. The dream about Slim

whipping his mother, for instance, sounds like something contrived by Slim to

amuse gullible readers, but Gifford lets it stand as gospel.

There

are plenty of gruesome details in Justin Gifford’s Street Poison, The

Biography of Iceberg Slim, but for every horrific moment of Slim’s life,

Gifford pauses the action to tell us about the importance of it all, or to

dryly recite a black history lesson, just to show how the mighty Iceberg Slim rose

above the racial climate of the day. A bit of this would go a long way, but

Gifford blurs the line between biographer and cheerleader, dulling some of the

book’s edges. Also, though Gifford tries to separate fact from fiction, he

allows some rather fantastic stories to go unchecked. The dream about Slim

whipping his mother, for instance, sounds like something contrived by Slim to

amuse gullible readers, but Gifford lets it stand as gospel.

Born

Robert Lee Moppins Jr. on August 4, 1918, and later known as Robert Beck, Iceberg Slim’s spent his formative years in

Milwaukee. While his mother worked as a beautician, the youngster spent many

afternoons admiring the various black pimps and whores sauntering in and out of

her shop. At a time when blacks wielded no influence, pimps had fat bankrolls,

dressed like cartoon kings, and drove Duesenbergs. Slim yearned for his own

stable of foxy whores. By his teen years he’d embarked on a life of petty theft

and rape, served time in reformatories, and ran with notorious characters with

names like Albert “Baby” Bell, and Joe “Party Time” Evans. Slim listened and

learned.

In 1941,

barely 23 but thoroughly poisoned by the streets, Slim landed in Chicago with

the intention of being a top pimp. Though he was occasionally overwhelmed by

older whores who were simply too vicious for him, he was soon one of the

reigning pimps in the city.

Pimping

was his calling. Even later, when he was nearly 70 and had long retired from

the street to pursue his writing career, there were rumors that he was still

pimping on the side. He always dressed the part, showing up for events and

interviews dressed like he was still in the game, favoring loud shirts and “an

electric pink suit that looked like aluminum foil.” Betty Mae Shew, a

kindhearted Texas woman who became Slim’s common law wife, not only helped type

his manuscripts, but also created his civilian pimp wardrobe, including the

cloth mask and goggles he wore on the old Joe Pyne show to maintain his sense

of mystery.

Gifford,

an associate professor of English literature at the University of Nevada, has

written previous books on black pulp writers and African American crime

fiction. He researched the hell out of Slim, and sharply portrays Slim’s

mercurial nature. Slim was a milk drinker who went to bed early, yet he was

also a junkie. He spent more than two decades manipulating women, yet, he felt

awkward on his first date with Betty Mae. His career defining debut memoir, Pimp: The Story of My Life, came about

because he’d grown too old for the game and needed some income. It was the long

suffering Betty Mae who convinced him to sell the gory tales of his past to a

publisher. An avid reader and autodidact, the aging pimp pursued writing with

the same fervor that helped him master the pimp life. There’s a joyous scene in

Street Poison where advance copies of

his first book arrive in the mail, inciting Betty Mae to dance around their

tiny home in celebration. When the money started to come in, Slim bought a 1948

Lincoln, a Great Dane named Leana, and a mink coat for Betty. Once a pimp…

Undoubtedly,

Iceberg Slim had some impact as a writer. One of his books, Trick Baby, was turned into a movie

during Hollywood’s Blaxploitation era. Slim was soon in demand as a lecturer,

and even recorded a spoken word album backed by the Red Holloway Quartet, which

supposedly influenced a future generation of hip-hop artists. Still, it’s

difficult to tell if Gifford exaggerates Slim’s influence, because the author

loves hyperbole. Not only does he resort to gross exaggeration when he

describes the Trick Baby movie as “a

major blockbuster film,” but he claims Slim’s writing brought on “cataclysmic

change.” That’s a mighty bold statement about an author whose books were sold

in barbershops.

What’s

admirable is that Slim managed to be a success in two different careers. Most

people barely make it in one field, never mind two. Slim’s reputation was such

that Tyson used to visit him back in the 1980s and ask for advice about women

(we all know how that worked out). But just as quickly as Tyson fell from

grace, so did Slim. He was constantly at odds with his publisher, an outfit

called Holloway House. (They went from publishing biographies of Jayne

Mansfield, to pornography, to black authors, in that order, which says a lot.)

Slim decided he’d rather not publish under Holloway’s banner than risk being

ripped off. Suddenly, unable to attract other publishers, he was broke. His

womanizing cost him the love of Betty Mae, who sold the mink coat and split.

Though he found another woman to marry, Slim lived his final years in L.A., an isolated

and sickly man peering out of his bedroom window with binoculars. He continued

to write, though, long, ultraviolent crime fantasias that Gifford reckons are

some of Slim’s best work. Iceberg Slim was, in the end, a writer. So he wrote.

Even as old age pummeled him, he wrote.

Gifford

covers a lot of ground, but he’s too smitten by Iceberg Slim’s rendition of

life on the streets, where black men taunted each other with vulgar poems,

killed each other, went to prison or went crazy, while black whores became

heroin addicts and wielded enormous knives. Everyone in Slim’s world seems a

hiccup away from homicide. Or suicide. When Gifford isn't feverishly recounting Slim's morbid past, he's

telling readers about the struggle of blacks in America. How many times does he tell us

that blacks were mistreated and had difficulty finding jobs? I lost count.

Of

course, some of the historical stuff is interesting. Did you know that Chicago

had such a big rat problem in 1940 that the city destroyed 30

tons of vermin in a citywide anti-rat campaign?

I also liked learning about Slim’s first common law wife, a tough gal

named “No Thumbs Helen” who eventually was locked away for murder. Yet, Gifford comes off as the sort of green

academic who is fascinated by the gloomier aspects of the poor. Gifford is

correct when he praises Slim for chronicling “new and original visions of black

underworlds that few have seen and lived to write about.” Yet, Gifford seems to

relish these tales of poverty and lowdown sex the way Bob Ripley collected

shrunken heads.

Gifford’s insistence that Iceberg Slim

was a genius is tough to digest. Gifford uses examples of Slim’s prose to

impress us, but they sound cumbersome and purple. Slim was not a great writer.

He was a hardworking, intelligent guy

who came along just as Holloway House was willing to take a chance on an unproven

black author. As for pimping, Gifford depicts Slim as a kind of master

psychologist, which is another hard sell, since the success of a pimp relies on

the simple knowledge that people are oversexed and stupid.

Even so, Iceberg Slim remains a

fascinating character. Maybe he’s not, as Gifford pleads, “One of the most

influential renegades of the twentieth century,” but he was one of a kind.

Dig? He’d probably be amused that a

white professor has written his biography, though it’s hard to forget Slim’s

quote about Chicago’s South Side. “The only white men I saw,” said Slim, “were

white men riding in cars looking for black pussy.”

- Don Stradley

No comments:

Post a Comment