What keeps Stripped Naked (2009) from being a great little low budget feature is that the filmmakers were trying to be serious. At least, I think they were. There's endless cursing in the movie, but no amount of vulgar language can fool audiences into thinking this simple tale of an exotic dancer who comes across $90,000.00 is actually Reservoir Dogs.

Cassie (Sarah Allen) is left on a roadside after an argument with her boyfriend Jack. She hitches a ride with a fellow who happens to be on his way to a major drug deal. There's a lot of gunplay, and Cassie finds herself holding the money and the drugs. Why, you may ask, did a guy on his way to a drug deal pick up a hitchhiker? That's just one of many dumb glitches in a movie filled with them. In a later scene, a hired hit man forgets to cock his gun, something a professional killer would certainly know how to do. By the end, a character who was barely a factor in the film's previous 75 minutes becomes the hero. If that's not bad enough, this is the sort of film where strippers dream of moving to Paris, and crime bosses actually sit in Naugahyde booths smoking cigars and sipping martinis.

What's most puzzling is that the movie feels afraid of itself. The violence is mostly off-screen, and for a story that takes place in a stripper's milieu, the movie is oddly sexless. All this movie knows about strippers is that they occasionally dance around poles, something we know from old Demi Moore movies. Cassie is never anything more than a moody bitch, so we never really care what happens to her. If she'd been some drug-addled skank, hoping to use the money to, say, help someone in her family, we might have rooted for her. As is, her fantasy of moving to Europe felt dumb and movieish. I kept thinking of the waitress in Pee Wee's Big Adventure. I also kept thinking of what Pam Grier could've done with the role.

Still, the movie has a sort of Red Bull and Vodka fueled energy, and there are at least two good performances, one by Tommie-Amber Pirie as a lesbian with a heart of gold, and Mark Slacke as an overly polite gunsel hired to find Cassie and reclaim the drug money. The movie is never dull, there are one or two plot twists that keep the thing going, and it isn't bad to look at. Director Lee Demarbre may actually be competent, but I'd advise him to visit a real strip club.

Still, the movie has a sort of Red Bull and Vodka fueled energy, and there are at least two good performances, one by Tommie-Amber Pirie as a lesbian with a heart of gold, and Mark Slacke as an overly polite gunsel hired to find Cassie and reclaim the drug money. The movie is never dull, there are one or two plot twists that keep the thing going, and it isn't bad to look at. Director Lee Demarbre may actually be competent, but I'd advise him to visit a real strip club.

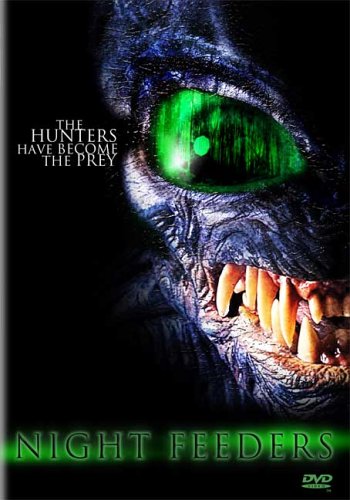

If Stripped Naked is aiming for a 1970s exploitation feel, Jet Eller's Night Feeders (2006) aims for a 1980s horror paperback, complete with jovial rednecks and flesh eating aliens. And it hits the bloody target. Granted, if you're aiming this low, you're likely to score. All you have to do in this sort of movie is keep the action going, and create some interesting creatures. The formula dates back to at least The Thing from Another World, or Invasion of the Saucer Men, the later of which feels like the great grandpa of Night Feeders.

If Stripped Naked is aiming for a 1970s exploitation feel, Jet Eller's Night Feeders (2006) aims for a 1980s horror paperback, complete with jovial rednecks and flesh eating aliens. And it hits the bloody target. Granted, if you're aiming this low, you're likely to score. All you have to do in this sort of movie is keep the action going, and create some interesting creatures. The formula dates back to at least The Thing from Another World, or Invasion of the Saucer Men, the later of which feels like the great grandpa of Night Feeders.

The story is standard stuff: a group of good ol' boys are out for a weekend of deer hunting, but they've set up their tents right where some space debris has landed. This "meteor" turns out to be a kind of space egg, hatching a dozen or more critters who are plenty hungry. They need only a few seconds to strip a man down to his femur. "Hush my mouth," says a redneck. "That aint no beaver!"

Joe Bob Briggs would be proud.

There are plenty of bloody stumps and chewed up human bones and late night chases through the woods. None of this is particularly scary, but it's fun. The movie likes itself. If it desires to be nothing more than a hillbilly wet dream for the Fangoria crowd, so be it.

Two things make it work. The creatures, for one, are excellent. They're wraithlike, like emaciated young raptors. Granted, every movie monster of the past two decades has looked more or less like a raptor, but these things are strangely compelling, especially when seen from a distance. They seem nervous and fidgety, as if they're so hungry they can't keep still. I also liked how they wailed at night, as if crying for their intergalactic mommy.

Second is Donnie Evans as the redneck who ends up facing down the alien menace. With nothing but a beer gut and a shotgun, Evans goes from being the movie's comic relief to its unlikely hero. He reminded me of the late great Dennis Burkley, who had a long career playing bikers and hillbillies. Donnie Evans should do the same.