REQUIEM FOR A HEAVYWEIGHT

Scott LeDoux fell harder than any of them

by Don Stradley

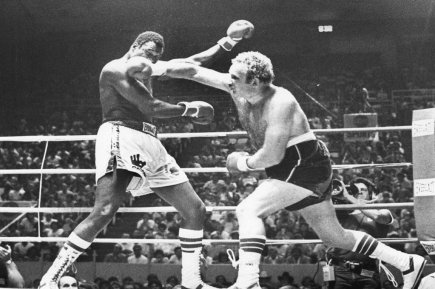

If there was ever a defining

moment in Scott Ledoux’s career, it may have happened in the sixth round of his

1980 bout with WBC heavyweight champion Larry Holmes. LeDoux, trapped in a

corner and taking punches, suddenly let fly with his right hand. It was a sweet

shot, the best he’d thrown all night. It was just enough to alert the crowd in

Bloomington Minnesota that their hometown contender, an ill-fated warrior who

had been promoted by Don King as some kind of boxing lumberjack, was returning

fire. Holmes, always susceptible to the right hand, wobbled like a man who had stepped in a pothole.

LeDoux winged another, but this time Holmes moved in with a right uppercut that

had some thumb on it. LeDoux fell to his knees, pawing at his eye. When referee

Davey Pearl stopped the fight in the next round, the vanquished LeDoux waved

his arms in protest, complaining that he’d been thumbed. That was LeDoux’s life

in microcosm – just as he was getting started, he caught one in the eyeball.

If there was ever a defining

moment in Scott Ledoux’s career, it may have happened in the sixth round of his

1980 bout with WBC heavyweight champion Larry Holmes. LeDoux, trapped in a

corner and taking punches, suddenly let fly with his right hand. It was a sweet

shot, the best he’d thrown all night. It was just enough to alert the crowd in

Bloomington Minnesota that their hometown contender, an ill-fated warrior who

had been promoted by Don King as some kind of boxing lumberjack, was returning

fire. Holmes, always susceptible to the right hand, wobbled like a man who had stepped in a pothole.

LeDoux winged another, but this time Holmes moved in with a right uppercut that

had some thumb on it. LeDoux fell to his knees, pawing at his eye. When referee

Davey Pearl stopped the fight in the next round, the vanquished LeDoux waved

his arms in protest, complaining that he’d been thumbed. That was LeDoux’s life

in microcosm – just as he was getting started, he caught one in the eyeball.“I don’t feel like a loser,” LeDoux said, reciting his unofficial mantra. “A loser is beaten, and I wasn’t beaten.”

And so it went throughout LeDoux’s career. LeDoux lost the big fights, and a lot of close decisions went the other way. Add to this his wife Sandy’s 10-year battle with cancer that lead to her early death. There was also the child with epilepsy, and LeDoux’ alcohol intake, and the way he pissed through money, and the way promoters used and abused him, and then his own death at 62 from Lou Gehrig’s Disease, the once mighty LeDoux spending his final years unable to tie his shoes or feed himself. Because of these unrelenting hardships, Paul Levy’s The Fighting Frenchman, a chronicle of LeDeoux’s life, is at times unbearable. LeDoux was boxing’s Job, constantly tested.

My favorite LeDoux line came when he was a commentator for ESPN. The talk had turned to punch stats, and LeDoux argued that left jabs shouldn’t be considered less important than a right cross. When he lost patience, he growled at some faceless stat counter. “Let me hit you with a left jab,” he said. “When you wake up, I’ll hit you with a right hand. Then you can compare.” It was a good line, not mentioned in Levy’s book, but there are plenty of others here, for LeDoux had a quick mouth, even between rounds. Once, after George Foreman spent three minutes lighting him up, LeDoux asked his trainer, “Is my forehead still in the front of my face?”

Levy’s book assures us, once again, that even the most ordinary lives harbor deep, unpleasant secrets. The wisecracking LeDoux had been born into a rough Minnesota family of drinkers and brawlers, and as a boy he’d been sexually molested by a local creep. LeDoux kept the encounter to himself for decades, though his inner turmoil manifested in other ways, namely a drinking problem, temper tantrums, and a masochistic fighting style. He carried his hands so low that he was essentially begging opponents to hit him. “I’m like concrete,” LeDoux often said, but anyone who presents himself as indestructible is usually hiding something; some hurts keep on hurting.

The Fighting Frenchman is filled with details about LeDoux’s jumpy psyche – the hysterical crying jags that came after losing bouts, the anger that saw LeDoux try to kick an opponent in the head after a bad decision (and inadvertently knock Howard Cosell’s wig off), and his occasional dips into race baiting, particularly before the Holmes bout. PC types of today would simply tag LeDoux a bigot, but he was too complex to dismiss with a kneejerk label. He was, Levy writes, “an emotional brute.”

There are some high points in the book, including LeDoux’ loving marriage to Sandy, and what was probably his greatest moment as a fighter, the 10-round draw with Ken Norton that ended with Norton dangling over the top rope, saved by the bell, one punch away from obliteration. But draws don’t get you a victory parade, and the book lacks any moment of triumph. (Even the Norton bout had the LeDoux stamp of hard luck on it – a woman in his hometown drove her Volkswagen into a pole that held the main artery for the local cable-TV hookup, destroying anyone’s chances of seeing LeDoux’s shining hour, unless they had the old-fashioned antennae and caught a few shadowy images.)

At what may have been his lowest ebb, a 42-year-old LeDoux was hired as a sparring partner for Mike Tyson. According to Levy, the padding had been removed from Tyson’s gloves, which resulted in LeDoux’s face being torn apart. “You could feel his fist,” LeDoux told Levy. LeDoux never blamed Tyson for boxing with altered gloves, maintaining that Tyson was a good man who had helped him when he needed money.

But how Tyson ended up with rigged gloves is a mystery in itself. The sparring session took place after Tyson’s loss to Buster Douglas, so maybe Tyson was trying to restore his reputation, putting sparring partners through more pain so the word would spread that Tyson was hitting harder than ever. Tyson was also an avowed admirer of old-time fighters who sometimes fought with rigged gloves. Perhaps he’d wanted to be Kid McCoy for a day, to see what sort of damage he could inflict. The incident shines a new light on something that happened years later, when Tyson enlisted Panama Lewis to work in his camp. Lewis, of course, was the disgraced trainer who lost his license in the 1980s after being found guilty of glove tampering. Levy doesn’t investigate the incident, content with LeDoux’s belief that the stuffing had been removed by Tyson’s trainer, Rich Giachetti. Tyson, LeDoux insisted, “wouldn’t have done a thing like that. He didn’t need to anyway.”

Letting the episode at Tyson’s camp go unexamined is one of many problems with Levy’s book. Though he spent 35 years at the Minnesota Tribune and has written for many reputable magazines, Levy’s style is clunky, undramatic. His fight descriptions are bland, as if he’s hurrying through them to get to more of LeDoux’s tragedies. He milks some suspense out of LeDoux’ eventual encounter with his childhood molester, and he successfully depicts LeDoux as a shambling hulk battling a lifetime of insecurities, but it’s as if Levy decided early on that LeDoux’s story was best painted in big, melancholy strokes. LeDoux comes off as a slug, crawling from one terrible moment to the next. That he eventually devoted his time to local politics and charity events doesn’t provide much uplift. (Even the acknowledgments are a downer, as Levy reveals that his own wife died during the writing of the book.)

To Levy’s credit, there’s no overplaying of LeDoux’s ability, no suggestion that he could’ve been a champion had things been different. Levy doesn’t hide LeDoux’s crusty side, either. When certain people remember LeDoux as cocky and disagreeable, Levy gives them their say, including Holmes, who remembered LeDoux as an “asshole.”

LeDoux’s final years, when he was confined to a wheelchair and oxygen tank, are given the usual flourishes, as his Minnesota fans rallied to help him pay his ever-growing medical bills. Yet, Levy seems to revel in the misfortune that comes to fighters, especially LeDoux’s former opponents, like Duane Bobick, who nearly lost his arms in a factory mishap, and Greg Page, strangled to death with his head stuck in the bars of his hospital bed.

Then again, what is a

boxing story without the grim stuff? Levy wants the ugly side of boxing in bold

relief to offset LeDoux the flawed everyman. “His fans adored him,” writes

Levy near the end, “because they thought he was one of them.” But this is too

grandiose, as the previous 200-plus pages made abundantly clear, because it

trivializes the rock-bottom gloom of Levy’s subject; it makes pretty the very

lightning bolts of misery that would, save for sturdy souls like LeDoux,

destroy us.