In films that focus on serial killers, it’s

rare that the killer himself is being stalked. Hell, that ruins the entire notion of

vicarious living for the teenage fans of these films, where semi-naked women are spied on

while they do filthy things, and destroyed for being so darn lovely and

unavailable. But in The Barber, an intriguing

and highly watchable little thriller, the killer is the target.

Francis Visser (Scott

Glenn) was once accused of killing 17 women.

When there wasn’t enough evidence to convict him, he moved

to a small town, changed his name to ‘Eugene Van Wingerdt’, and lives out his

days as the neighborhood barber. The

police chief and the waitresses at the local diner adore the old coot. Why not? He’s a slightly fragile grandpa figure who

dresses neatly, never curses, and dispenses wisdom to anyone within

earshot. He has a kind word for everyone, and even takes in local hoods

and teaches them how to cut hair. He’s a nice guy.

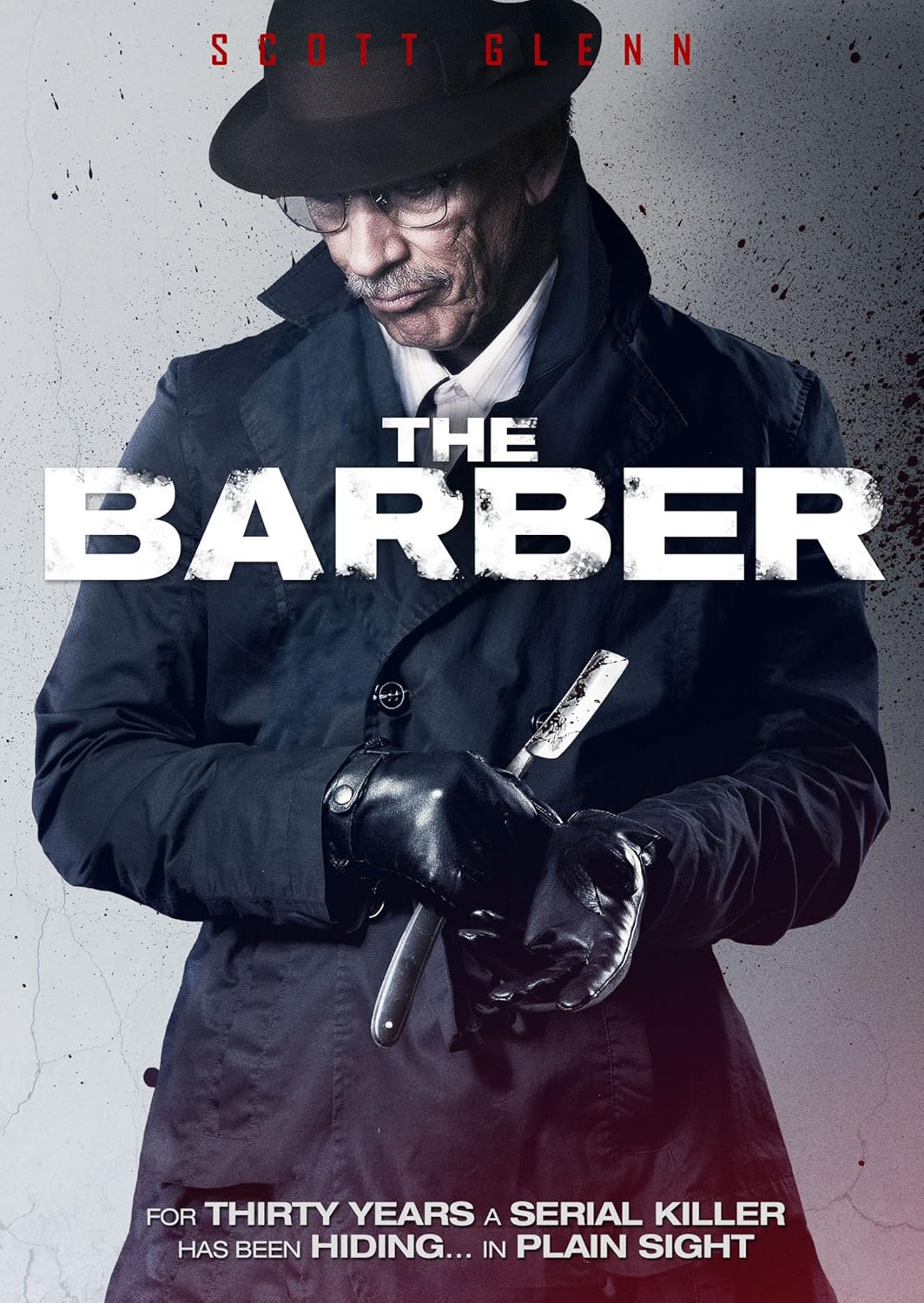

The difficulty in creating a character that is supposed to

be nebulous is that we all know Scott Glenn, still a

tough piece of rope at age 70, is not fragile at all. Plus, the posters for the

movie show him grinning slyly while wielding a straight razor. So when a young troublemaker named John McCormack (Chris

Coy) arrives in town demanding that Eugene teach him the finer points of serial

murder, we assume that the town’s beloved haircutter is probably not the sweetheart he

pretends to be.

The standard serial killer movie ends with the bad guy

getting his comeuppance; he killed a

bunch of women, demented teenage boys in the audience got their jollies, but inevitably the murderer has to fall

to his death, or be shot by Jody Foster. Normalcy

is restored, and we can all go home knowing that serial

killers are just bogey men to be stuffed back into the closet. Of course, sometimes the killer lives, just in case there's a sequel to be made, but he usually gets it in the end. For a while they were killed in unique ways, crushed in trash compactors, or fed to crocodiles, but a bullet works just as well and seems more gritty. Meanwhile, The Barber ends with a twist right out of

a 'Tales from the Crypt' episode, and even though you can see it coming from

miles away, it’s still satisfying in an old EC comic book kind of way.

McCormack, you see, isn’t exactly a serial killer in training. But I’ll leave it to you to find out what he’s

all about.

Eugene learns to relish McCormack’s company. He especially

enjoys teaching him the tricks of his old trade, such as how to look at his watch when picking up a hitchhiker, just to show

that he’s really in a hurry and is only stopping to help out of the goodness of

his heart. Eugene shows McCormack how to

be a murderous fiend with the same pride and attention to detail as an old samurai would

prepare a rookie for battle.

Glenn, who has long been one of our most reliable and

charismatic character actors, is the key to the movie’s success. He’s fascinating, whether he’s referring to a

potential victim as “yummy,” or he’s simply shuffling around the barber shop in

his old-man act. The movie wouldn’t be

half as good without him, for it’s probably the most sexless and least violent

of any serial killer movie I’ve ever seen. Director Basil Owies (making his feature debut

after a number of short films) and veteran screenwriter Max Enscoe seem

uninterested in the usual serial killer fare. Eugene doesn’t appear to crave his victims

physically – he just takes them to a deserted area and buries them alive. The only real violence we see in the movie is

when various male characters start slugging it out, or attacking each other with baseball bats. It’s as if Owies and Enscoe, at heart, wanted

to make a simple cop movie with lots of revenge and ass-kicking and Latino men

shouting “motherfucker” across a crowded bar.

But that’s a mild quibble. The movie works better than most,

features some good acting (I especially liked Stephen Tobolowsky as a police

chief who looks like a harmless old wreck but harbors some violent instincts of

his own), and there are enough plot twists to keep you wondering. True, you might forget the whole thing as soon as the final

credits roll, but for 95 minutes you are in the world of The Barber. It’s not a

bad place to be.

- Don Stradley