EXCELLENT NEW BIOGRAPHY SHOWS THE QUIET BEATLE AS A FULLY FORMED HUMAN CHARACTER, NOT JUST A PIOUS ROCK STAR...

EXCELLENT NEW BIOGRAPHY SHOWS THE QUIET BEATLE AS A FULLY FORMED HUMAN CHARACTER, NOT JUST A PIOUS ROCK STAR...

by Don Stradley

There

are at least a half dozen new biographies of George Harrison listed on

Amazon, including one by his older sister, and one by his first wife. Other

Harrison bios include a lovely coffee table book based on the well-made but

rather safe HBO documentary by Martin Scorsese, and others with

titles like ‘Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George

Harrison’, and ‘Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of

George Harrison’. I’m not even counting the various kindle-only editions

and reissues of older books. If the quiet Beatle knew how his past was

being picked over, he’d be annoyed. His first song written for the Beatles,

after all, was titled ‘Don’t Bother Me’.

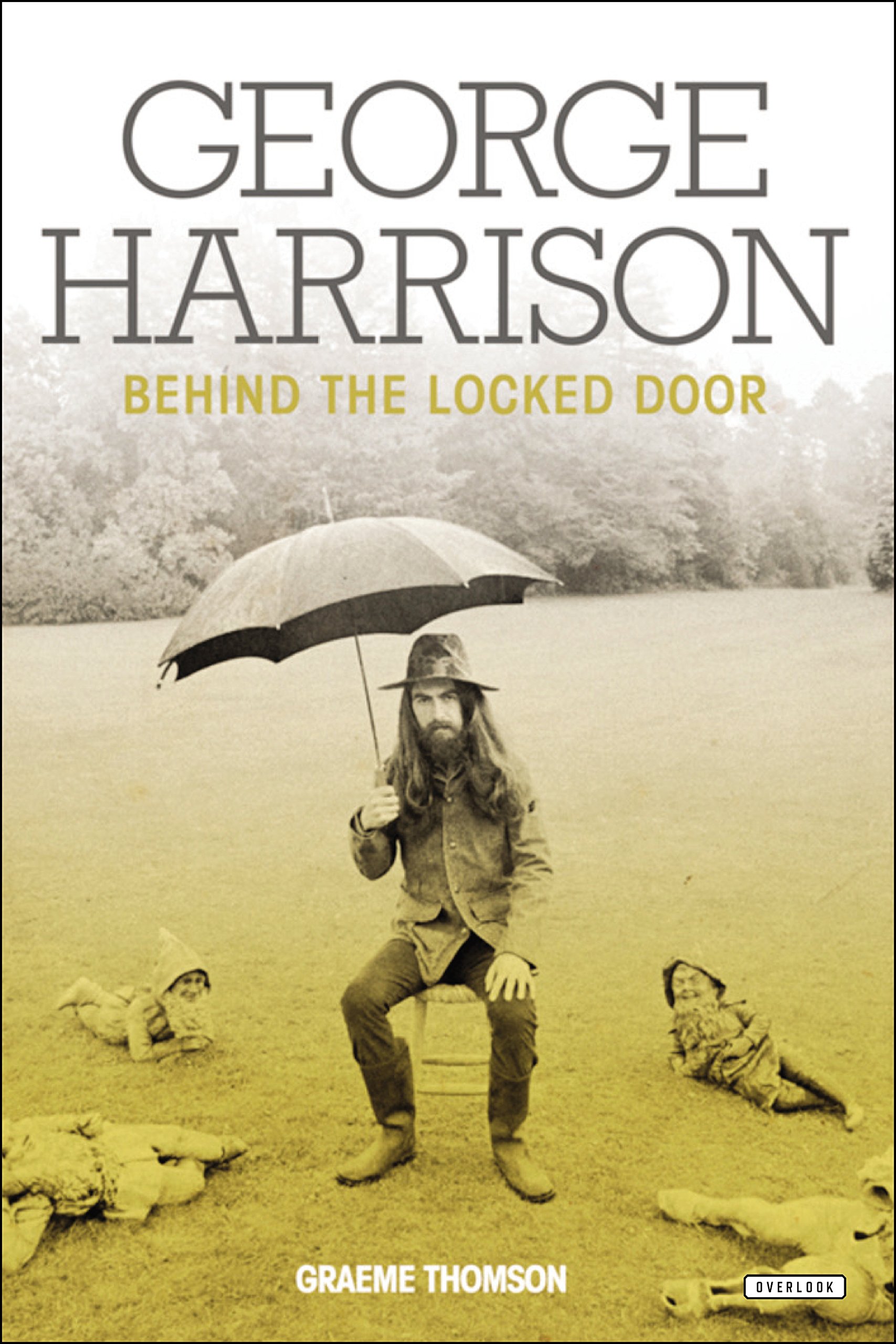

‘Behind

the Locked Door’ by Graeme Thomson is probably as good as it gets when

it comes to documenting George Harrison. Then again, how do we know? Beatle

books have a sameness to them, and by now, more than 50 years after the band

hit America, the stories are developing a cut and paste feel. I could

read five or six George bios, and probably patch together a reasonable bio on

my own, without having to visit Liverpool or interview some elderly sound

engineer who could offer such tidbits as ‘Well, George always wore nice shoes,

you know.’ The vaults, I believe, are empty. Any author attempting a

Beatle bio is going to need a spectacular voice and a hell of a point of view

to make his work stand out. Thomson succeeds on most fronts, giving us a

more developed and three dimensional Harrison than the one we usually get,

including the one Scorsese gave us.

George,

we learn from Thomson, was a bit of a rebel, though a good lad at heart. He was

fond of his mum and dad, and once he became a famous Beatle, his mum would

invite scores of adoring female fans into the Harrison home to show off her

son’s old bedroom. Now and then they girls would help her with the laundry. She

was a smart ol’ gal, this Louise Harrison. It’s funny to imagine a house

full of little female Beatle fans, dutifully helping Louise iron George’s

socks.

George

discovered the guitar at age 12, and would cling to it like a life raft for

most of his life. Harrison mastered many styles, from Chuck Berry to Chet

Atkins to the heavy slide playing that dominated much of his later playing.

Though a recent memoir by Beatles recording engineer Geoff Emerick,

described Harrison as a fumbler who struggled with his instrument, Thomson

portrays Harrison as a careful craftsman who made each note count. It’s

also of interest that more than one musician quoted in the book says that

Harrison always sounded better when he was just mucking around with his guitar

in a hotel room or at his home, than he did in a recording studio.

The

problem, of course, was that George was the youngest of the Beatles,

stuck in the role of little brother for the band’s duration. John Lennon and

Paul McCartney were not just older, but they were brilliant songwriters and

singers. George’s guitar was a significant part of the group’s sound, but

songwriters get the royalties, not guitarists. Hence, George tried to

write songs, often with forgettable results. Lennon and McCartney could

write a hit on their lunch break. Harrison, meanwhile, spent months on a

tune, and would only write about things that were deeply personal.

With workmanlike diligence, he gradually learned the craft.

By the time the Beatles broke up, he’d written some of their most beautiful

songs. That he went from singing Carl Perkins’ ‘Matchbox’ to writing and

singing ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ is one of the most impressive creative

arcs in the history of rock music.

Thomson,

who has written for various music publications in the U.K., gives us the edgier

aspects of Harrison, too. George was a bit of a womanizer, and a drinker,

and despite his yearning for spiritual growth, could be as selfish and

demanding as any spoiled rock star. He wasn’t always generous about

giving credit where it was due, and his treatment of some Moog representatives

in the late 1960s was deplorable. He was so sheltered that he didn’t know

how to use a locker or a pay phone. He claimed that being a Beatle had

been a nightmare, yet he never hesitated to play the Beatle card when

trying to seduce a woman or get a good seat in a restaurant. He could be

surprisingly kind, yet casually cruel.

And, of

course, there were his friendships with Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan, which

actually seemed more emotional and volatile than anything he may have had with

his fellow Beatles. Clapton fell in love with Harrison’s first wife,

Patty Boyd, and there ensued a decade long game of sexual one-upmanship between

the guitarists. Harrison’s friendship with Dylan is less fiery, but just

as interesting. It’s as if Harrison wanted to replace Lennon and

McCartney with the one man who might have been a greater songwriter, and become

his pal to boot. According to Thomson, Harrison would record hours of

himself covering Dylan tunes in his home studio. Could there someday be a

CD of Harrison doing Dylan?

Yet,

this uneducated Liverpool boy, “a real wacker” as Lennon called him,

would go on to be a galvanizing entertainment force once the Beatles had ended,

first with the wondrous recordings on All Things Must Pass, then with his epic

Madison Square Garden charity concert for Bangladesh, then as a movie

producer and head of Handmade Films, and again in the 1980s as the

founder of the Travelling Wilburys, a dream group featuring Harrison, Dylan,

Tom Petty, Roy Orbison, and Jeff Lynne.

Thomson

covers all of these victorious moments, and also the defeats, such as

Harrison’s troubled 1974 tour of North America, the plagiarism lawsuit around

‘My Sweet Lord’, and his struggles for commercial success in the era of disco

and punk. He sees Harrison as constantly toiling, even as he was beset

with a creeping fogeyism; by age 34, Harrison was content to putter in his

garden and sneer at the new sounds he heard. Thomson suggests Harrison could

have enjoyed greater success in the 1970s, if only he’d given his fans a bit of

what they wanted. “Had he popped up on Top of the Pops,” Thomson writes,

“wearing his Krishna hat, a smile and a pair of bright trousers he might have

scored a few more brownie points.”

Then,

there was Harrison’s interest in Eastern religions, which either made him

a source of fascination or a subject of derision, depending on your take.

It’s been forgotten by now, but there was a time when Harrison was perceived as

a pious ‘holier than thou’ type shoving that dreary Indian music down our

throats, especially by critics at Rolling Stone. But the disdain of

critics was nothing compared to the eternal battle raging within Harrison, as

he “would ping pong back and forth between the sacred and the profane,

going slightly further in either direction each time.”

Thomson

structures the book as if Harrison’s career reached a pinnacle with the

Bangladesh concert, and that everything to follow was an anti-climax. There’s

some accuracy in this, and no doubt Thomson makes it seem as if the concert,

where Harrison rallied a dozen or more of his pop star friends to help raise

money for monsoon victims, was a truly heaven-touched event. “Forty years

later,” he writes, “it shines like a beacon of practical, clear-headed,

empathetic activism amid the bed-ins, bagism and myriad woolly gestures of the

age which generated lots of heat but very little light.”

I like

Thomson’s writing. It never takes off on any wild flights of inspiration, but

in a plain-spoken and quite effective manner he tells the tale he

sets out to tell, that of a boy who dropped out of school to join a band with

his much older mates, a boy who “was far from stupid, but by comparison his

creativity and intelligence was much rougher around the edges, a little less

consciously artful.” The boy grew up to seek God, and struggled mightily

as he bounced back and forth between the material world and the

spiritual. Thomson also deserves credit for writing about

Harrison’s interest in India in a way that never bores. Harrison’s sad end,

which included a home invasion attack by a demented Beatles’ fan (Harrison’s

worst nightmare, dating back to the 1960s, had come true), is handled

tastefully, with just enough attention to detail to satisfy.

The more

we know about the Beatles, the bigger the puzzle grows, and there will always

seem to be missing pieces. In ‘Behind The Locked Door’, Lennon comes off as

distant, and two-faced. McCartney comes off as a hurricane creative

force, but a bully. Ringo Starr seemed to be a friend, and according to one

chapter, was still supplying Harrison with drugs well into the 1980s.

George? I ended up liking him. Sure, he was prickly at times, but by the book’s

end he seemed to become a decent fellow, a man with the courage of his

convictions, even if it took him years to reach that point. I

particularly liked reading about how he treated the ‘apple scruffs,’

those loyal young girls who hung around the gate of Abbey Road studios

hoping for a glimpse of their heroes. George would occasionally bring them

tea, or stop to say hello. How his attention must have thrilled

them!

Yet, he

may have seen something of himself in those girls, wide-eyed and slightly

innocent, yearning for something more meaningful than what existed on their own

side of the gate.

No comments:

Post a Comment