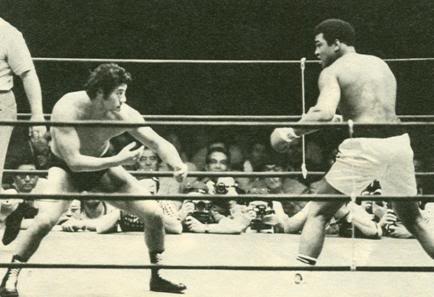

FORTY YEARS AGO ALI TANGLED WITH A WRESTLER

But why bring it up?

By Don Stradley

But why bring it up?

By Don Stradley

Despite

the laborious title of Josh Gross’ ALI vs INOKI: The Forgotten Fight That

Inspired Mixed Martial Arts and Launched Sports Entertainment, I’m not convinced that Ali’s fiasco with a

Japanese wrestler in 1976 inspired or launched anything. There’d been mixed

boxer/wrestler matches going back several decades, and as for “sports

entertainment,” the coy term for professional wrestling, there’d been enormously

popular wrestling events long before the Ali - Inoki debacle. Hell, in 1934

Strangler Lewis wrestled Jim Londos in front of 35,275 at Wrigley Field. Still,

Ali-Inoki is a large link in a very long chain, and as such, deserves a closer

look than it’s generally given.

Despite

the laborious title of Josh Gross’ ALI vs INOKI: The Forgotten Fight That

Inspired Mixed Martial Arts and Launched Sports Entertainment, I’m not convinced that Ali’s fiasco with a

Japanese wrestler in 1976 inspired or launched anything. There’d been mixed

boxer/wrestler matches going back several decades, and as for “sports

entertainment,” the coy term for professional wrestling, there’d been enormously

popular wrestling events long before the Ali - Inoki debacle. Hell, in 1934

Strangler Lewis wrestled Jim Londos in front of 35,275 at Wrigley Field. Still,

Ali-Inoki is a large link in a very long chain, and as such, deserves a closer

look than it’s generally given.

You

couldn’t ask for a closer look than the one Gross gives this odd footnote in

sports history, but the tone is problematic. Depending on the reader’s

interest, one might be put off by Gross, a longtime MMA journalist, who is

clearly more interested in mixed martial arts than boxing. While Gross reminds

us constantly that boxers haven’t fared well in mixed rules bouts, he doesn’t

acknowledge that a few boxers have knocked MMA men goofy. And while he

interviewed quite a few wrestling and MMA types for his book, including an

insignificant “writer” from the WWE, he didn’t speak to quite so many boxing

people. One whose input is sorely missed – Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee – is

long dead.

Inoki

was an interesting character - he was as hungry

for fame as Hulk Hogan and Vincent K. McMahon combined, and was knowledgeable about

real fighting techniques as well as American-style ring theatrics – but kept

himself blanketed in mystery. Was he really Korean, as some suspected? Was he affiliated

with gangsters, as many in the Japanese wrestling world are said to have been?

He played the role of noble athlete, but anyone who spends 15 rounds trying to

kick Ali in the nuts is certainly no boy scout. Then there was the bizarre New

Year’s Eve ritual where Inoki’s most devoted admirers would stand in line

waiting to be slapped in the face by their hero. It was, recalls Bas Rutten in

the book’s intro, a “hard” slap. This was a sort of spiritual exercise, where

Inoki would supposedly transmit some of his fighting spirit into his fans. Call

me a misguided Westerner, but I’ve never

wanted Lennox Lewis to hit me in the mouth for luck.

The Ali-

Inoki debacle took place during one of the worst years of Ali’s career. After

the watershed period of 1974-75, Ali’s popularity was at its highest in ‘76,

but he was showing signs of age, and even burnout. Ali had wanted to fight in

Japan and had fished around for a Japanese boxer, but when Inoki’s promotional

company contacted him with an offer, he saw it as a chance to partake in the

ballyhoo of professional wrestling. As for the question of who would win

between a boxer and a wrestler, I can’t imagine anyone over the age of 12

concerning themselves with it. But according to Gross, this question has tormented mankind for

centuries. Though Ali used it as a promotional crutch, I doubt he was seriously thinking about it. It’s more likely

he wanted to get away from boxing for a bit because he needed a distraction,

something whimsical to draw money. Ali had, as Dr. Ferdie Pacheco said, “the

blood of a con artist.”

Where

things went haywire was in establishing rules for the event. Inoki was unhappy when

Ali’s camp demanded certain martial arts tactics be banned, but he knew being linked with Ali was worth a

few concessions. The bout, which took place at the legendary Budokan Hall in

Tokyo, was pure shit. Inoki stayed low, butt-scooting across the ring, kicking

at Ali’s legs. Ali spent the entire 15 rounds yelling at Inoki, unsure of how

to deal with the crablike character in front of him. Far more entertaining was

what Ali did stateside to promote the match, which included workouts

with wrestling journeymen Buddy Wolff and Kenny Jaye. With “Fearless” Freddie

Blassie as his “manager,” Ali would throw big, exaggerated uppercuts and the

goons would rocket skyward like villains in a Bugs Bunny cartoon. At least it was

funny.

Whether or not Ali-Inoki was legitimate is a puzzle Gross can't solve. For one thing, he relies too much on the memories of crackpots. Can I really trust someone like "Judo" Gene LeBell, who made much of his living in the pro wrestling racket? That it was declared a draw suggests some sort of fix was in,

particularly since Ali landed no more than a few punches. To paraphrase Pacheco, someone was going to get fucked, and it wasn't going to be Ali. My own hunch is that Inoki knew in

advance that the bout would be called a draw, so he decided to just kick the

crap out of Ali’s legs, not to win, but to send Ali home with some lumps and bruises. As for what Ali knew or thought, no one can say for

certain. Inoki’s refusal to be interviewed for the book says a lot, too.

And, of

course, there was the aftermath, with Ali calling Inoki a coward (I rather

enjoyed the accounts of Ali taunting Inoki with some brutal American street

talk, the sort that would get him banned from Twitter). For his part, Inoki

claimed Ali’s hands were taped in a way that would make his punches too

dangerous, hence, his strategy of staying on the canvas. Jhoon Rhee, the

heralded taekwondo master

who helped train Ali, suggested that Ali and Inoki had been scared of each

other, not sure of what the other might do. And the public, feeling bamboozled,

quickly forgot Ali-Inoki had ever happened.

Yet,

Ali-Inoki would occasionally rise from the ashes. Inoki kept the boxer-wrestler

concept going with bouts against Check Wepner and Leon Spinks (and even a

white-haired Karl Mildenberger), while Ali kept a hand in the wrestling biz by

appearing as a referee at the first WrestleMania in 1985. The growing interest

in MMA during the 2000s lead to Ali-Inoki being hailed, somewhat generously,

as a kind of groundbreaker. If nothing else, Ali-Inoki showed future MMA

promoters what to avoid.

Gross

covers all the bases. In fact, he covers too many bases, trying to squeeze in a

history of pro wrestling in both America and Japan, plus a history of MMA.

Despite Gross’ ambition, he lacks finesse. He gets carried away with insider

fluff, like a blow invented by Rhee, “that melds thought and action into

high-speed data flow.” He’s convincing when he suggests the bout was so badly

received because Inoki’s kicking style was lost on American audiences, and he does a good job reminding us of the event's publicity blitz - it was the Ali event of the summer, and was hyped like any of his heavyweight title bouts - but Gross

remains an MMA mark, wallowing in stories about broken shinbones and dislocated shoulders; he’s like a

dreamy kid who just saw his first Bruce Lee movie.

And

every time he refers to Ali’s punches as “strikes,” I wanted to scream.

Gross,

who has covered MMA since 2000, is also clueless when it comes to the pro

wrestling side of the story. He strangely refers to Gorgeous George as a

“reformed psychiatrist from New York City,” which still has me scratching my

head. My favorite clinker, though, was when he mentions a bout between Inoki

and Andre the Giant as “probably all fake.” Wow, do you think so?

He gets

some amusing anecdotes from people on Ali’s team, namely Pacheco, Gene Kilroy, and Rhee, who tells of Ali asking him to set

up a rendezvous with a Korean woman after the match, even as Ali’s legs were,

according to publicist Bobby Goodman, “so swollen he couldn’t put his pants

on.”

But, as

always, it’s Ali himself who stands out. Exhausted after the bout, surrounded by an entourage of

bloodsuckers that numbered nearly 50 by this time, his legs covered in ice packs, Ali growled at a New York

Times reporter that boxers were “so

superior to rasslers. Inoki didn’t stand up and fight like a man. If he had

gotten into hittin’ range, I’d a burned him but good.” The irony, lost on Ali (and Gross) is that

many boxers had said similar things about Ali, that his constant

movement in the ring was somehow unmanly, and that if he’d stood still they

would’ve nailed him. Now Ali knew how it felt to be Jerry Quarry.

As for

Inoki, I keep thinking about matches from late in his career. In what could be

seen as his own version of Ali’s "rope-a-dope," the 50ish Inoki would take a

prolonged pounding, but at the last

moment he’d pin his opponent, and then collapse. His seconds would rush

into the ring, wrap him in his robe and take him away, a bit like the climax

of a James Brown concert. Inoki’s fans ate it up, roaring as if they’d

just witnessed something majestic. Inoki would move slowly down the aisle, his fans

trying to touch him, fans who hadn’t even been born when Inoki met Ali, fans

who may not have realized, or cared, that most of Inoki’s career was utter show

business, but were still standing in line, waiting to be slapped.

No comments:

Post a Comment