Prior

to Chrissie Hynde, women in rock came in two shades, either frilly earth mama,

or sex kitten. Patti Smith? Too literary. Joan Jett? Bubblegum. Heart? Deborah

Harry? Janis Joplin? Grace Slick? All excellent, but all strongly feminine.

Hynde was different. She wanted to strut like the male rock gods of the 1960s. She didn’t want to be Carly Simon; she

wanted to be Keith Richards.

A

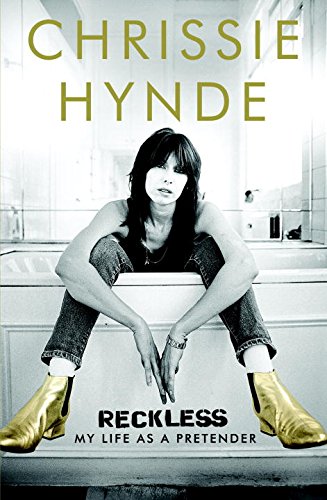

third of the way into her compelling new memoir, Reckless: My Life As A Pretender, Hynde

interrupts her swift narrative to remind readers that the rock life doesn’t

come without peril, and that her formative years were spent under the influence

of hard drugs.

“I

was well and truly fucked up most of the time, or at best, reeling from the

effects of the day before. I don’t like how much this story is influenced by

them, but they were the defining characteristic of my generation. And all our

heroes. And in the end, this story is a story of drug abuse.”

By

turns cynical and playful, humorous and

gloomy, Hynde, now 64, writes with

candor about the years leading up to the formation of The Pretenders, one of

the great bands to come out of the late 1970s. The result is an almost Forrest

Gumpian story about a young woman always landing in the lap of history. There she is, a

16-year-old watching David Bowie at the Cleveland Music Hall, and then,

inexplicably, she’s in Bowie’s limousine. Then she’s at Kent State when the National

Guard lets loose with gunfire. Mexico, Toronto, Paris, London, she’s

everywhere, on a dime, sleeping on floors, prowling, observing. It’s not all

fun, though. There’s a major generation gap between Hynde and her parents,

there’s a foul encounter with a biker gang that leaves her humiliated and frightened, and financial struggles that force

her to develop the survival instincts of a cockroach. Yet, there she is,

plucked from obscurity to write for England’s New Musical Express. There she is

on the fringes of early punk, mingling with The Sex Pistols, The Clash, and The

Damned. She offers quickie snapshots of the various people she meets, the

numerous guitar heroes, scene makers, and drifters, but her most vivid

recollections are saved for the band members who helped Hynde realize her rock

and roll ascendancy.

Reckless, which Hynde wrote without the aid of a ghost writer, is

not just a music diary. It’s also a time capsule, looking back at the days when the Pill

allowed casual sex to explode along with the music that was dominating the

radio waves. And it’s the story of one woman’s strange, often painful journey

through two decades, a journey that seems punctuated by death and wretchedness,

to start a band that would kiss fame on the mouth but not get to go all the

way, told without the self-importance that usually infects most rock star

memoirs.

Pretenders

fans, of course, may wish for more detailed discussion of Hynde’s talent, but

she doesn’t hold herself up as a great artist, claiming only that the punk era

allowed primitives like her to be heard. Any “elation” she felt after writing a

song quickly turned into “anxiety”, for she feared she’d never write another

one. Hynde’s humility is touching, but a bit more insider stuff would’ve been

welcome. Then again, maybe she was too high to remember what happened.

Hynde’s

prose is like her songwriting. It bristles, it bops, it rarely keeps to a

standard time signature. Just as The Pretenders could mix rough rockers with

tender ballads, she turns in chapters that are energetic and wild, next to

sections that are bittersweet and, in some cases, enigmatic. But she’s not the

tough rocker chick we’ve always imagined. She’s a bit of an insecure bumbler;

she actually waited for both of her parents to die before she sat down to write

her story. The bad girl we thought we knew, despite dropping several F-bombs,

is nowhere in sight.

Though

life in The Pretenders was frustrating, it was initially joyful. When, after

years of trying to form a band, Hynde finally meets James Honeyman-Scott,

Martin Chambers, and Pete Farndon, it’s as if an orphan has finally found a

home. Some of Hynde’s most enjoyable writing is when she winsomely recalls

Honeyman-Scott’s guitar playing, how he “oozed melody,” and how he made her

“more than I could have ever been on my own.”

Hynde

started out as a pensive child who enjoyed long solitary walks around Akron,

and spent her time on the grammar school playground pretending to be a horse

named Royal Miss, “carefully avoiding the area where the rest of the girls in

our class were watching the boys play kickball.” From there, like most kids of

the 1960s, she became entrenched in the groovy new sounds on the radio, an

experience enhanced by growing up in Ohio, where the radio ruled. Concerts,

too, were vital. Seeing Mitch Ryder perform gave her a peek at her own future.

“He

was a mesmerizing showman in his blousy pirate shirt and dress pants, his belt

buckle slung to the side, resting provocatively on his hip bone. Slinky.” Just

like Hynde would look years later on an album cover.

She

also was a girl who put off womanhood as long as possible, not having sex until

she was 19, but quickly finding herself in and out of the clap clinic.

Her

ideal man was the stereotypical scrawny English rocker, and she eventually linked up with

one: Ray Davies of The Kinks. She recalls their stormy relationship as “a battle of

wills,” but it gets no more coverage than the time Hynde tried

to make a cup of tea for Brian Eno. A marriage, a cup of tea, an ugly scene in

Memphis where she kicked out the windows of a cop car, none of this gets more

than a page or two, as if Hynde treats

each event like a three minute single.

A

recurring theme in the book is the idea of kismet. Coincidental run ins with

people who would help her, from journalist Nick Kent to Motörhead’s Lemmy, all

seem strangely preordained. Granted, London was a small town, but it seems odd

that she kept falling in with people who turned out to be so important to her

success. “How can we prove that anything is arbitrary?” she writes.

Another

frequent topic is Hynde’s ambivalence about female roles. “The idea of trying

to be sexy was repellent to me, something I’d never deliberately do.” All her

life she prided herself on being “like a guy,” with quick reflexes and street

savvy, yet bass-playing boyfriend Farndon once bullied her into sharing a

songwriting credit he didn’t deserve, and Hynde admits to not only crying over

various men, but that in her younger days she wasn’t far removed from being a

generic, man-hungry barfly fueled up on Mad Dog 20/20, “the wino’s tipple of

choice.”

But

what was it about being in a band? At one point she writes, “The funny thing

about my unyielding desire to be in a band was that I really had no idea what I

was going for. I just knew it had to be hard, not soft. I never liked soft

things. Hard for me, every time: tea, strong; coffee, black; ice cream, frozen,

not melty. Rock? Hard, not soft; aggressive, unapologetic, masculine – that was

it.”

During

the worst times, Hynde describes her bandmates as “depraved drug fiends,” and

“sadistic little shits,” with every sound check becoming “a battle for

dominance.” She describes herself as no less depraved, citing the time renowned

degenerate Johnny Thunders, whom Hynde credits with bringing heroin into the UK

music scene, once warned her to pull herself together. Meanwhile, photographers

desperately doctored band photos to cover up Farndon’s “green pallor of

smack.”

Farndon’s

decline was horrific. Dumped by Hynde as a lover, he continued as The Pretenders’

bassist but grew nasty, violent. Friction between Farndon and Honeyman-Scott

increased, while Hynde tried to keep the peace.

“Pete’s

junkie persona had taken over and was inhabiting him,” Hynde writes, “like a

demonic possession.”

Hynde’s

descriptions of people in her circle are pinpoint. She describes Johnny Rotten,

whom she almost married so she could stay in England, as “a real little bastard

when he wanted to be.” Of Lemmy, she writes that he was “hip to the trip and

didn’t touch anything except amphetamines, smoke, and Jack Daniel’s.” Iggy Pop,

with whom Hynde had a brief dalliance, had eyes like “a sea of green with a

bloodshot sun rising.” Her accounts of Honeyman-Scott farting on cue make us

wish we’d known the guy.

Just

as the band’s momentum was building, Honeyman-Scott died of a cocaine heart

attack. Farndon died in a bathtub with a needle in his arm. “There’s your rock

and roll ending,” Hynde writes. “I’d taken him into my reckless world and lost

him there.” Though Hynde would continue performing and recording with various

people backing her, the original Pretenders lineup was sui generis. That Hynde ends her story in 1984 says a lot.

Farndon’s

death still weighs on Hynde, but the fun-loving and brilliant Honeyman-Scott is

the book’s most haunting figure. Long before she knew him, Hynde heard

Honeyman-Scott playing guitar in a house next door while she was staying in

Wales. And that’s what gives this story its gloomy edge. Hynde claims that

Honeyman-Scott had been hovering around her life for more than a year before

they actually met. Though she never turns mawkish, Hynde still marvels at the kismet

that brought them together.

“I

remembered someone playing some sweet guitar and wondering who it was,” she

writes of that strange day in Wales. "I could hear his unique sound floating

over the gardens and into my room; he had been near me all along.”

It’s

enough to make you believe in destiny. That’s why The Pretenders’ saga is among the saddest of showbiz tragedies.

- Don Stradley

- Don Stradley

No comments:

Post a Comment