John L.

Sullivan has only been represented a couple of times in movies, most notably by

brawny Ward Bond in Gentleman Jim. Bond did a fair job of swaggering,

but there was more to Sullivan than strolling into a bar and shouting that he

could lick any son of a bitch in the place. As we learn in

Christopher Klein’s Strong Boy, Sullivan was not only the

heavyweight boxing champion for 10 years, but lived a life that would make

Floyd Mayweather and Mike Tyson look like Boy Scouts.

From the

start, Sullivan had the very modern philosophy of “go big or go home.”

For instance, the name “John Sullivan” was generic, even during the 1880s when

he first came into the public view, but the insertion of the middle initial “L”

gave it flair. He wanted you to know that he wasn’t just any John

Sullivan from Boston. He was the strongest man on whatever continent he trod

upon, and could level you with one blow from his meaty right hand, a shot

described by one opponent thusly: “I thought that a telegraph pole had

been shoved against me endways.”

Of

course, newspapers loved Sullivan. Whether he was crushing some opponent

in the ring, or drinking his way through a new town, he was good copy. “My

excesses have always been exaggerated,” Sullivan said. But he added, “I

am public property, and the press is free to say of me what it pleases.”

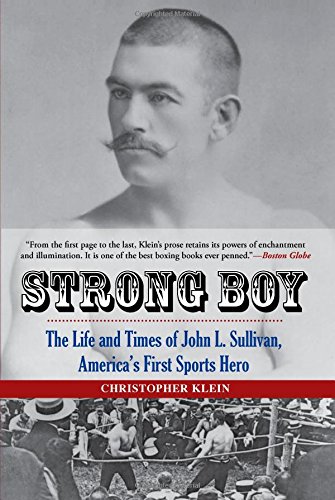

Klein’s

tasteful, well-written biography chronicles an extraordinary American life and

quietly tries to separate the truth from the folklore. Strong

Boy reads like a concise American epic, starting with the influx of

Irish immigrants in the 1800s. Klein doesn’t delve into Sullivan’s psyche, but

is content to report on what Sullivan did and said, letting us draw our own

conclusions. The author touches on Sullivan’s well-known racism, but

doesn’t dwell on it. Perhaps Klein felt that focusing on Sullivan’s

“drawing of the color line” in regards to his career would dilute

Sullivan’s historical importance. A more daring writer might have

offered more insights into the touchy subject, but Klein seems squeamish, even

writing Sullivan’s favorite slur as "n-----".

Still,

the book is packed with great moments: Sullivan whipping Paddy Ryan in

New Orleans for the American championship in 1882; the time in 1881 when

he fought John Flood, “The Bulls Head Terror”, on a Hudson River barge;

his ambitious “knockout tour” of the country, when he brought his growing

legend to the hinterlands; brawling for several hours under the boiling

Mississippi sun to turn back challenger Jake Kilrain in 1889; and his

surprising success on the theatrical stage, when Sullivan happily learned that

his drawing power remained strong long after his retirement from the ring.

Sullivan’s

highs were matched, and some would say trumped, by spectacular lows, including

drunken conduct that is still embarrassing to read about more than a century

later; and an egomaniacal streak that can only be ascribed to Sullivan

not only reading his own press, but believing it. “The American publicity

machine and celebrity culture was beginning to crank,” Klein writes, “and John

L. knew how to pull the levers.”

It must

be said, though, that Sullivan was worthy of the hype. He not only popularized

gloved boxing, but managed to dominate his weight class while fighting under

both the London bareknuckle ring rules, and the newer Queensberry rules, which

is roughly comparable to fighting successfully in both MMA matches and

boxing. And not only did he do it at a time when the police were always

trying to shut down fights, and opponents wore spiked boots and thought

nothing of cutting into your legs and feet, but he was usually nursing a

hangover.

Klein’s

book is well-done, but there are some minor shortcomings. Like some

previous Sullivan biographers, he ends the tale with Sullivan’s 1918

funeral, when the frozen ground at Mount Calvary Cemetery had to be

blasted with dynamite. That’s a fine place to end the story, but

surely there was some legacy to be discussed. Klein is fine at

syphoning material from old archives, but his own thoughts are as absent from

the story as are black fighters from Sullivan’s record.

There

are also occasional lapses into purple prose. “Sullivan’s broad jaw,” Klein

writes, “was as solid as the granite chiseled from the quarries of his native

New England.” Lord, that’s a tough one to swallow. Fortunately,

most of the florid stuff comes early, as if Klein is clearing his mind of fluff

before getting ready for the later chapters, which are nicely written.

But not even Klein can make the potato famine interesting.

Anyone

writing about the life of John L. Sullivan will be confronted by holes in the

story. The traditional narrative arc of how this young man came out of

Boston with hurricane force, became a larger than life jerk, and then mellowed into

a gentleman pig farmer, has always struck me as slightly contrived. Was

he really so content in retirement? Were Sullivan’s early days entirely without

signs of the whirlwind to come? Klein sometimes mentions Sullivan’s

generosity, but gives few significant details. Sullivan’s

friendship with George Dixon, a black bantamweight known in the papers as

“Little Chocolate”, would’ve been ripe for discussion, but again, Klein touches

on it and moves along.

But

then, Sullivan has receded so far back into mythology that his biographers are

compelled to avoid the murkier stuff in favor of the more obvious

points. As Klein writes of Sullivan capturing the heavyweight title, “No

Bostonians celebrated more than the Irish, who had felt blistered by the red-hot

Brahmin scorn since their arrival. Now, one of their own was champion of

America. Sullivan instantly became an Irish-American idol, one of the country’s

first ethnic heroes.”

True

enough. But it’s not enough. The Sullivan saga is not merely, as many

claim, a product of the time in which he lived. His tale is so primal that

we’ve seen it replayed by other fighters, from Jack Dempsey, to

Muhammad Ali, to Tyson, dominant ring men with oversized personalities who

turned out to be all too human. There is something of the fable in

Sullivan’s life, something distinctly American, about a man who had it all,

lost it all, and became a better person. He’s a big American figure who

deserves a big American book. But until someone can write it, Klein’s version

will do.

- Don Stradley

No comments:

Post a Comment