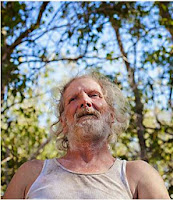

The opening of Joe belongs to Gary Poulter. He's playing G-Daawg, the sinister town drunk. He's sitting on the ground, being berated by his son (Tye Sheridan). Poulter sits there quietly, taking the abuse. We get the feeling he's heard it all before. He seems pathetic, his face mapped by a lifetime of screw ups. Then, like a cobra, Poulter cracks the kid in the face with a slap that shakes the walls of the theater. Then he rises and ambles away, stumbling up a hill. Some men are waiting for him. He acts as if he might walk past them, but they knock him to the ground and kick the hell out of him. He stays on the ground, defeated but still alive. This is Poulter's movie debut. How many other actors get you instantly hooked this way? And he hadn't said a word yet.

Director David Gordon Green wanted real faces in his movie, so casting agents scoped the Austin, Texas area for earthy types who might serve as extras. Poulter was at a bus stop, scrounging around, close enough to overhear the agents having a conversation. When Poulter realized what they were doing in Austin, he approached them. "I'm an actor," he bellowed. It was sort of true. He'd appeared as an extra many years ago on a 1980s TV show. Now he earned dimes as a "street performer," break dancing and doing monologues from old Vincent Price movies. But that wasn't what grabbed the attention of these Hollywood types. Poulter was only 53 or so, but looked 73, with a chunk of his ear and most of his teeth missing. He could dance a little, and speak Japanese, and talked like a machine gun spewing gravel. There had to be a place for him in this movie. As one of the casting agents would say later, you can't fake cirrhosis of the liver. Hence, Poulter was cast as G-Daawg, the conniving murderous runt whose son prefers the company of an ex-con played by Nicolas Cage.

G-Daawg is every homeless alcoholic who has made you uncomfortable, the one who corners you and leans in a bit too close when he asks for money, the one who appears too drunk to stand but can still pick your pocket. He's the one who dances in the street for spare change, gets a few laughs from the tourists, but then you'll read about him doing something horrible. G-Daawg is the embodiment of America's broken underclass, a delusional sort who probably hasn't bathed in a month, but is vain enough to own a jacket with his name embroidered across the back.

Green considered Poulter for a small role in the film, but after spending time with him, he knew he had found his G-Daawg. There were concerns, though. Could Poulter be trusted? Would he even show up to the set? Poulter's family assured Green that he wasn't a bad guy, just a bit roughed up from life. He'd sober up for a while, but his addictions to drugs and alcohol were hard to kick. He was also bipolar, and had known the sort of hard times that would bury most people. He was a lot like G-Daawg. Somehow, Poulter took the role and not only showed up on time, but nearly made himself the centerpiece of the movie. When the production wrapped, Poulter was imagining a new career for himself. There was talk of him appearing in a film being shot in New Mexico. For once, there was some upside to Poulter's life.

Mere weeks after Joe wrapped, Poulter was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died shortly after the diagnosis. Austin police found him face down at the edge of Lady Bird Lake. The camp of homeless men he'd been staying with knew he'd been in jail a few years earlier, busted for breaking into a Chipotle's restaurant.

He hadn't told them he'd been in a movie.

***

There aren't many actors who appear in one movie, steal every scene they're in, and are never heard from again. But it's not entirely unheard of. Vittorio De Sica, the great Italian director, often cast unknowns in his films. He believed that everyone had one role they could play convincingly. When casting the main player in Umberto D. (1952), De Sica chose Carlo Battisti, a 70-year-old professor from the University of Florence. Battisti, who had never acted before, was incredibly moving as an elderly homeless man wandering the streets with his dog, searching for shelter.

Many of De Sica's other "discoveries" went on to appear in more films, but Battisti never acted again.

Harold Russell was an untrained actor when William Wyler cast him as a returning war vet in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Russell had lost his hands in the war and made a striking impression as Homer Parish, a Navy vet fitted with metal hooks. Russell was awarded with an honorary Oscar, and an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor, the only time anyone has ever won two Oscars for the same role. Other than a few bit parts many decades later, Russell didn't pursue acting. On Wyler's advice, Russell went back to college, "because there wasn't much call for a guy with no hands in the motion picture industry."

Harold Russell. Carlo Battisti. One role you're born to play.

Gary Poulter. G-Daawg.

***

There's a scene in Joe that is absolutely spellbinding. G-Daawg is sitting on the sidewalk, as usual, when a frumpy old drunk stumbles past, clutching a bottle of vile looking stuff. G-Daawg spots him, starts following. He's as creepy as a giant boa seizing up a small monkey.

Whatcha got there? What are you drinking?

The old guy pays no attention. He sits under a tree and starts guzzling. G-Daawg starts talking, making up a story about his wife being at the hospital. He gets philosophical. A person just don't know from one day to the next which one is going to be their last....G-Daawg spins a phony tale of his wife's illness, and how he comes into town to check on her, and to have a little drink, too, because there aint nothing wrong with nobody having themselves a little drink now and then...Meanwhile, G-Daawg spots a long iron rod sticking up out of the dirt, a wicked looking thing with double pointed prongs, like devil horns. As he talks he paws at it with his foot, digging it out. Then he picks it up and bashes the old rum-pot in the head a dozen times. Just a few scenes earlier, G-Daawg had been fumbling around on a job, too weak to swing a hammer. Now, craving the alcohol in his victim's hand, he strikes like an avenger. When the man is dead, G-Daawg gently kisses his forehead. He takes a swig from the bottle and walks away.

Even Poulter's walk added something to the film. Slightly splay footed, like Charlie Chaplin, taking those shuffling steps familiar to people with bad hips, or a busted equilibrium. In a scene where he dances, he doesn't show grace and rhythm, but a sort of crazed movement that may have once been watchable but is now just ugly, heavy, like an old piece of machinery breaking down. The film is loaded with great performances, but Poulter's presence permeates the movie. He radiates bitterness and bad times. In the novel by Larry Brown, G-Dawg is described only as "the old man." He's horrid by his actions. Poulter makes the character into a human scavenger, wandering crookedly through a daylight hell.

"It was important not just to show the despicable side of him, even as the novel goes into extremely brutal detail," Green said during the Joe press junket. "I wanted to show the broken side of him, to find the sadness in a character that was so aggressively repulsive." When the shooting was over, Green gave Poulter a new set of teeth as a parting gift.

Poulter was a rookie, but he was a fast learner. He seemed to say, Put the camera on me and I'll give you something. Watch the way he digs through a dumpster for food like a manic rat, or the way he burns holes into Cage's character with his thousand-mile stare. This is an actor finding his groove, holding nothing back. Some of his scenes made producers weep. Poulter's younger sister told an Austin newspaper that the film was difficult to watch. "Gary's not even acting," she said. "That's so totally him."

Poulter loved being in the movie. He even showed up on days when he wasn't needed, just to watch. Cage liked his sense of humor, and the two bonded over a mutual love of heavy metal music. The crew liked him. He was funny, and could break up the monotony of a movie set. Poulter liked to joke that he didn't need any special makeup to play a beaten old homeless guy.

Green says a lot of material was shot of Poulter that will end up on the Joe DVD as an extra feature. Poulter would unleash anything that came to his mind. The more seasoned actors would just lay back and let him rip. They didn't want to stop him; it was like watching a volcano boil over.

The movie people looked after Poulter, moving him into a hotel so he wouldn't be homeless during the shoot. They provided him with a lap top. He communicated with distant family members via Skype. Someone even set him up on that modern fool's parade known as Facebook. When doctors told him he didn't have much longer to live, he posted "...talk about your peeks and valleys..."

Then he was gone. He stopped posting on Facebook, was no longer in touch with his family. Hotel life was too expensive, he said. Time to hit the road again, where he'd been before the movie people found him.

February 19, 2013 was Poulter's last day on Earth. He spent his final moments standing at the edge of Lady Bird Lake, a place where tourists come to watch the bat population. There are over a million bats at Lady Bird Lake. Maybe some flew overhead as Poulter stood there, not far from a statue honoring Austin blues legend Stevie Ray Vaughan. Maybe he was thinking about the weather. The winter had been mild, but there was talk of snowstorms building up along the panhandle. Maybe he thought about his illness. Maybe he was too drunk to think about anything.

Poulter had been staying at a camp with some other homeless men. According to Austintexas.gov, there are approximately 2300 homeless Austinites. Some sleep in cars. Some gather at popular tourist spots like the lake, as Poulter did. On his last night, Poulter wandered away from the group to urinate. He stood at the edge of the lake, unzipped his pants, then fell face first in the muck. That's where he died. The death certificate said "accidental drowning with acute ethanol intoxication". A person just don't know from one day to the next which one is going to be their last.

The men he'd been with at the camp knew nothing about Poulter, other than he'd done a little prison time. That's how it is on the streets. You talk about the hard times, so they know you belong there.

He didn't mention that he'd been in a movie, or that he'd made Nicolas Cage laugh. Maybe he didn't think they'd believe him. Or maybe, looking back on it, being in a movie wasn't such a big deal. Hell, it was just a role he'd been born to play.