If it's true that everyone who bought the first Velvet Underground album went on to start a band, then it may also be true that they've all written biographies of Lou Reed. There have been at least a dozen in recent years, each as unsatisfying as the last, with authors not sure if they should focus more on Reed's weird sex life, or how smart it was for him to combine Hubert Selby with rock and roll. They're torn between condemning his rotten behavior, or worshiping him. This is always a problem when an artist is deserving of praise and appreciation, but also happens to be a jerk.

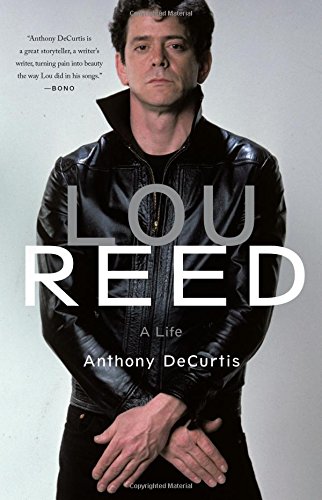

Anthony De Curtis is the latest to take up the task, but there's a problem with Lou Reed: A Life. DeCurtis smartly avoids the usual mistake made by Reed's biographers, in that he doesn't try to match Reed's verbal daring. The downside is that he's too tasteful, too careful. It's not totally his fault, because no writer has ever successfully captured Reed. Still, DeCurtis' measured style feels anemic when discussing a songwriter who, in his late 60s was still writing lyrics like, "The two whores sucked his nipples 'til he came on their feet."

As a teenager, Reed seemed like a character out of a Patricia Highsmith novel, a naughty Long Island boy in a crew neck sweater who played on the school's tennis team, read voraciously, and sneaked off to gay bars. His parents feared he was not only gay, but possibly schizophrenic, so in what was a reasonably acceptable thing to do at the time, attempted to curb Lou's queer ways by subjecting him to electroshock therapy. He came home from these treatments, his sister described, "unable to walk, stupor like."

During these strange years, Reed discovered rock and roll, enrolled in Syracuse University where he fell under the sway of poet Delmore Schwartz, and later worked as a staff songwriter for Pickwick records, a company that distributed made-to-order records by cashing in on whatever was hot at the time (ie surfing, bikers, etc). Learning that ostrich feathers were to become a craze, Reed wrote a song called "The Ostrich." When the company hired musicians to play the thing, in walked John Cale, who would soon be Reed's partner in the Velvet Underground. By now, Reed was already writing songs like "Heroin," which he obviously kept from the bosses at Pickwick. He and Cale would play it on street corners, which must've been a hoot for the tourists.

DeCurtis, a longtime contributing editor at Rolling Stone, gives us the Lou Reed that he wants to give us, a sort of wounded genius who was actually quite nice underneath the angst. It's not the air-brushed version of Reed that was done by PBS' American Masters back in the 1990s - DeCurtis includes some of Reed's lower moments, like the time he had a homeless fellow physically removed from a bank kiosk, and his immature treatment of guitarist Robert Quine - but DeCurtis' version of Reed feels somewhat pampered. Yes, Reed was horrible at times, but, as DeCurtis suggests, his past shaped the man he became. Besides, he ended up with a nice home in the Hamptons with Laurie Anderson. If a few women got beat up along the way, well, we still have Rock and Roll Animal.

Then there's Reed's two-year relationship with the enigmatic Rachel, the towering transsexual who remains one of the enduring mysteries of the Reed saga. DeCurtis gives Rachel more coverage than most biographers, but there's still room for speculation. Was she a hooker? During the '70s, Reed had a penchant for interviewing the transvestite whores in Times Square, and one wonders if Rachel had been one of his subjects. Reed's feelings for Rachel were never in doubt, though once he met second wife Sylvia Morales, Rachel was dismissed quicker than a drummer who had missed a cue. There must be an enterprising author out there who can write Lou & Rachel: The Glass Coffee Table Years. (Read the book and you'll get the reference...)

Reed's ability to constantly rise from defeat, first from the ashes of the Velvets as a strange glam rocker, later as a prickly elder statesman who could still compose challenging music well into his 40s and 50s, made him a rarity in the rock business. Even the albums that didn't sell well at first were eventually hailed as classics. The Velvets were given the dubious honor of being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, though Reed wasn't enshrined for his solo work until after his death, which was an astonishing oversight.

DeCurtis gives us a lot to consider, but he also leaves out some things. Reed's movie work, for instance, gets no coverage at all, not his contribution to Ralph Bakshi's Rock & Rule (1983), or his role in Paul Simon's One Trick Pony (1980), or his portrayal of a loopy folk singer in Get Crazy (1983), or his funny cameo in Blue in the Face (1995). There's no mention that Reed's music appears on 258 soundtracks, or that "Perfect Day" became a huge UK hit in 1997. Perhaps DeCurtis felt these items weren't worth mentioning, though he found space for every one of Reed's stinking Tai Chi instructors, and Reed's love of a nice prosciutto.Maybe, like all Reed biographers, DeCurtis simply couldn't figure out how to cram it all in.

DeCurtis also seems too pleased with his own relationship with Reed, noting a bunch of meaningless encounters at restaurants and concerts, and assuring readers that "my having a PhD in American literature, writing for Rolling Stone, and teaching at a prestigious college all meant a great deal to him, though that's the sort of thing he would never admit." There's no explanation of how DeCurtis knew what Reed was thinking, unless another of his achievements is the ability to read minds.

The book is not totally without merit, though. The best parts are when DeCurtis examines Reed's odd relationship with his father, who seemed to have been abusive enough to leave Reed permanently in search of daddy figures, from Schwartz, to Andy Warhol, to Doc Pomus. "The horror he had always felt about his father's imagined vengefulness was there," he writes about "Junior Dad," written by Reed as he neared 70, "along with an unnerving empathy." Oddly, some of DeCurtis' liveliest writing is when he chronicles Lulu, Reed's 2011 collaboration with Metallica, especially the "sonic impact" of their live performances that left the father of punk and the kings of metal "sweaty and beaming."

Still, DeCurtis is guilty of bending the Reed story to fit his theme, which has something to do with Reed's redemption, how he learned to love wholly, and then, when his body failed after years of abuse, faced death bravely. He paints Reed as a flawed man, a kind of martyr. "If Reed occasionally went too far," he writes, "personally or artistically, that was just the price that had to be paid for everyone else not going far enough." He even excuses Reed's violent streak as "cathartic, a necessary purging of the inessential, rather than offensive."

Right. Tell that to Reed's first wife.

The book is not totally without merit, though. The best parts are when DeCurtis examines Reed's odd relationship with his father, who seemed to have been abusive enough to leave Reed permanently in search of daddy figures, from Schwartz, to Andy Warhol, to Doc Pomus. "The horror he had always felt about his father's imagined vengefulness was there," he writes about "Junior Dad," written by Reed as he neared 70, "along with an unnerving empathy." Oddly, some of DeCurtis' liveliest writing is when he chronicles Lulu, Reed's 2011 collaboration with Metallica, especially the "sonic impact" of their live performances that left the father of punk and the kings of metal "sweaty and beaming."

Still, DeCurtis is guilty of bending the Reed story to fit his theme, which has something to do with Reed's redemption, how he learned to love wholly, and then, when his body failed after years of abuse, faced death bravely. He paints Reed as a flawed man, a kind of martyr. "If Reed occasionally went too far," he writes, "personally or artistically, that was just the price that had to be paid for everyone else not going far enough." He even excuses Reed's violent streak as "cathartic, a necessary purging of the inessential, rather than offensive."

Right. Tell that to Reed's first wife.

DeCurtis gives a lot of thought to "Street Hassle," deservedly so because it is one of Reed's masterpieces. He observes that the song is likely an ode to Rachel, and notes how Reed's final, heartbreaking verse includes the line, "How I miss him, baby." As DeCurtis says, it is probably the only rock song in history where a male expresses his love for another male, which was quite daring of Reed. But DeCurtis misses something key. I've listened to dozens of Reed bootlegs and have noticed that starting around 1980 or so, Reed left that final bit out. He could still sing the parts about prostitutes and overdoses and the hopelessness of life and love, but not that last, haunting line.

Ultimately, DeCurtis offers some good insights, but a lot of mush, too. The secret to writing about Reed has yet to be solved. Should it be two parts music, one part personal life? Should it be all music? No one knows. Reed always kept us guessing when he lived. It's no different now that he's dead.

Ultimately, DeCurtis offers some good insights, but a lot of mush, too. The secret to writing about Reed has yet to be solved. Should it be two parts music, one part personal life? Should it be all music? No one knows. Reed always kept us guessing when he lived. It's no different now that he's dead.

No comments:

Post a Comment