Hell's Belle

A master of true crime writes about one savage lady

by Don Stradley

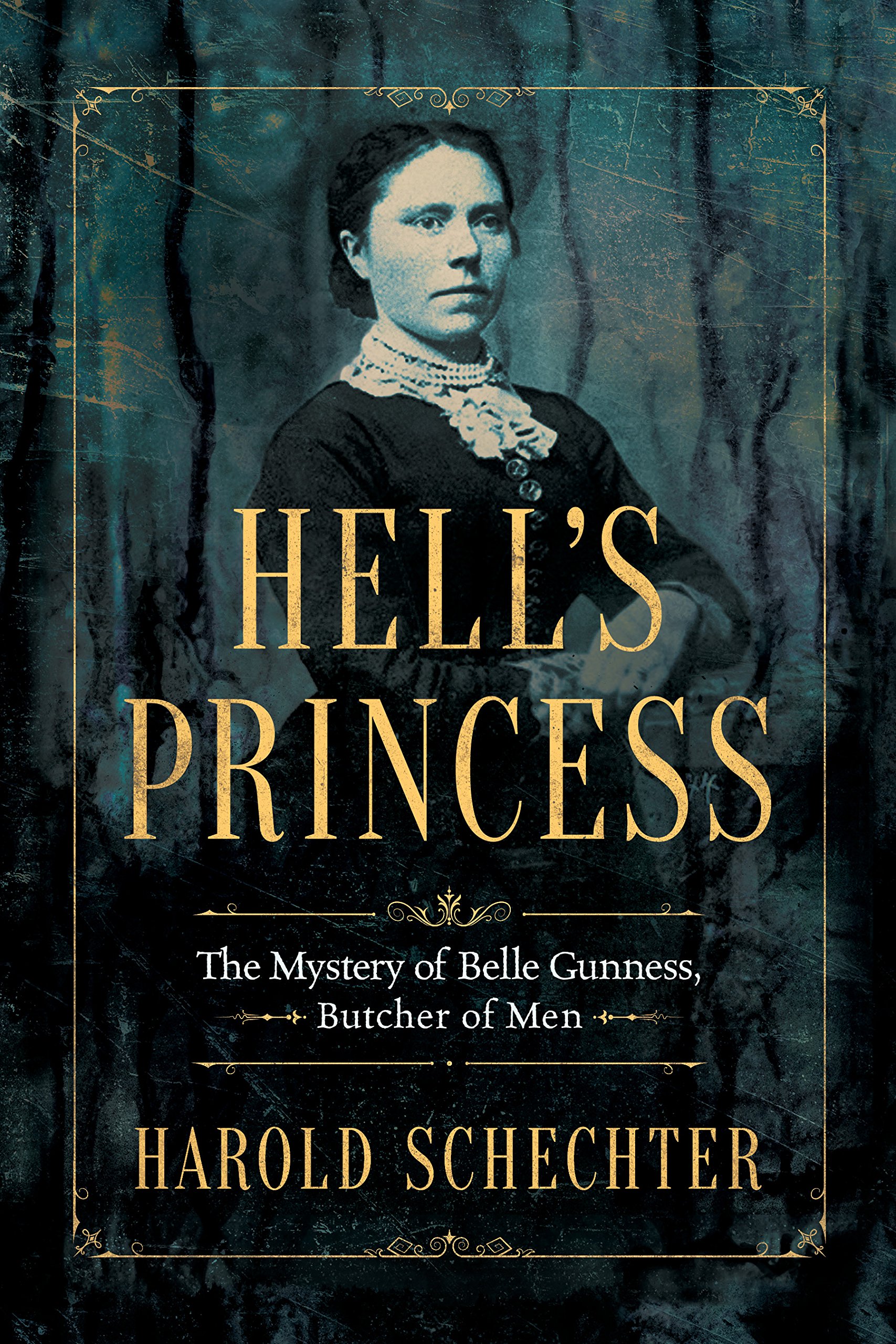

When people ask why a cheerful, clear-eyed fellow such as myself is so interested in ghastly crimes of the past, I refer them to Harold Schechter. What Bert Sugar was to boxing, what Charles Bukowski was to drinking alone, what Laura Hillenbrand was to Seabiscuit, so is Schechter to murderers, especially the American brand. His latest, Hell's Princess, is another master class in combining history with ghoulishness. In it, Schechter goes deep into the colorful saga of Belle Gunness, the La Porte, Indiana woman whose crimes shocked America more than a century ago. At the peak of her depravity, husbands and farmhands tended to die around her, either from poison or a crushed skull. Or both. By the time investigators dug up her "murder farm," the body count set a record that wouldn't be broken until John Wayne Gacy's vile exploits 70 years later. Belle Gunness was the Babe Ruth of serial murder, right down to her massive gut and the way she captured the country's imagination.

When people ask why a cheerful, clear-eyed fellow such as myself is so interested in ghastly crimes of the past, I refer them to Harold Schechter. What Bert Sugar was to boxing, what Charles Bukowski was to drinking alone, what Laura Hillenbrand was to Seabiscuit, so is Schechter to murderers, especially the American brand. His latest, Hell's Princess, is another master class in combining history with ghoulishness. In it, Schechter goes deep into the colorful saga of Belle Gunness, the La Porte, Indiana woman whose crimes shocked America more than a century ago. At the peak of her depravity, husbands and farmhands tended to die around her, either from poison or a crushed skull. Or both. By the time investigators dug up her "murder farm," the body count set a record that wouldn't be broken until John Wayne Gacy's vile exploits 70 years later. Belle Gunness was the Babe Ruth of serial murder, right down to her massive gut and the way she captured the country's imagination.The Belle Gunness style was as sly as it was blunt. Posing as a helpless woman, she'd post ads in local newspapers looking for a partner to help run her farm. Men, usually Norwegians like Gunness, answered these ads by the dozen. At Belle's insistence, they'd empty out their savings and cash in their insurance policies. Belle was waiting, with her arsenic and her axe. She knew how to extract money from dumb men, but Schechter insists that, "greed alone could not account for the sheer savagery of her crimes, the evident gusto with which she slaughtered her victims like farm animals." When the public learned of her murders, the frenzy of interest lead to the Gunness house, which had mysteriously burned down, to became something like a carnival attraction, with vendors selling ice cream as digging crews uncovered mutilated corpses. "Many visitors brought Kodaks and took their own photos," Schechter writes, "posing their families before the ruins of Belle's farmhouse or at the edges of the pits on the excavated hog lot."

What makes the story different from most, and what no doubt provided a challenge for Schechter, is that Gunness vanishes halfway into the narrative. The focus then turns to Ray Lamphere, a scrawny halfwit who may have assisted her in disposing of bodies, may have been her lover, and may have set her place on fire. The second half of the book is a flurry of false confessions and deathbed delirium. No one knows what happened. Did she die in the fire? Did she stage the inferno and escape? Did Lamphere kill her? Ultimately, Gunness becomes a figure of evil, as one historian put it, "whose malevolence seemed to match that of the unseen beings peopling Norwegian folk tradition."

Schechter has been producing books like this one since the late '80s true crime boom. I remember his early efforts, garish little paperbacks about Ed Gein and Albert Fish. He even wrote an intriguing book about the history of violent entertainment called Savage Pastimes, which had him exploring everything from cap pistols to public whippings. Though Hell's Princess ends with a shrug - Schechter is mystified as to what may have happened to Gunness - it's still a strong read, full of strange old characters from the 19o0s, a time of mustachioed sheriffs in polka dot bow-ties, exploitative newspaper publishers who blended fact with fiction, a time when the old world was still encroaching on the new, when psychologists of the day, or alienists as they were called, made observations based on the shape of a person's head, and came to the generally accepted conclusion that Belle Gunness was an "evolutionary throwback...born by some hereditary glitch into the modern world," a woman with dead emotions, yet one with undeniable allure for lonely men of the Midwest and the cold prairie states. They were pushovers for a simple farm woman who wrote in her letters, Come to me and be my best friend forever.

https://www.amazon.com/author/donstradley

No comments:

Post a Comment