UP ALL NIGHT WITH THE REAL MIDNIGHT RAMBLER

Wilson Picket; stop and kick it

by Don Stradley

Wilson Picket; stop and kick it

by Don Stradley

Fletcher's telling of the Pickett story is as detailed and evenhanded as a reader could want, but even though Pickett is depicted as a genuine artist and a key figure of sixties soul, it's hard to disassociate the man onstage with the vile person he was at home. Fletcher points out that some of the stories about Pickett are exaggerations, but there are enough living people from Pickett's circle who will attest that he never met a promoter he couldn't berate, or a woman he couldn't turn into a punching bag.

Pickett's penchant for violence (he once attacked a female companion with a metal folding chair and beat her senseless) seemed embedded in his psyche from an early age. His mother, Lena, was especially vicious; she once responded to Pickett's refusal to do his chores by breaking his arm with a log. Pickett's brother Maxwell puts a forgiving spin on such brutal child-rearing when he tells Fletcher that black families in the South "were under so much stress...it would just release, in fits of rage and anger."

In between whippings, Pickett discovered a love for gospel music. He sang regularly at Jericho Baptist in his hometown of Prattville, Alabama, astonishing congregations with his already well-developed lung power. At the age of 15 Pickett joined the Great Migration of southern blacks, landing in Detroit to live with his father and new step-mother. Pickett soon had his own wife and child to support (and whoop on). Fortunately, the music business was thriving in Detroit, and young Pickett figured singing for money was better than going back to Alabama to pick cotton. "Wilson was so aggressive," said Eddy Floyd, whose group the Falcons soon hired Pickett, "he wasn't gonna be denied."

He jumped from group to group, from city to city, sticking with one combo for a while but always sneaking out to do solo gigs on the side. He was creating a unique style, which cut through the do-wop and Elvis imitators of the period, by blending his gospel background with some heated up rhythm and blues. He was no balladeer, and he didn't give a whack about being the next Nat King Cole. He was out to make his name, and he wanted to crush anyone in his path. His screaming style was a way of challenging any pretenders to what he imagined was his throne. The 1960s saw the hits pouring out of him like lava: "In The Midnight Hour," "Land of 1,000 Dances," "Funky Broadway," "Mustang Sally," and even a volcanic cover of The Beatles' "Hey Jude" with Duane Allman on guitar. His touch was so sure that he could even cover the Archies' "Sugar Sugar" and make it sound like a dangerous piece of funk. Still, the guy was never satisfied. By the 1980s he was known more for his alcohol and cocaine binges, not to mention his ever present handgun, than his string of unforgettable soul hits.

Fletcher, who has written some very fine biographies, shows us the good, the bad, and the hideous. When Picket wasn't beating up the women in his life - a practice he continued until he was too old and sickly to make a fist - he was boiling over with drug-induced paranoia, and waving his gun around like a lunatic. Of course, various people remember him as a sweetheart and a musical genius, a handsome man with perfect teeth, but it's telling that one of the best parts of the book is when bassist Kevin Walker grows tired of Pickett's bullying and hits him in the face with a metal towel rack, sending "Wicked Pickett" to the hospital with permanent eye damage. You may cheer for Walker to hit Pickett again.

Pickett had a bit of a comeback - these stories always feature the return from the ashes - and was occasionally featured in a documentary, or on Late Night with David Letterman, or would be called upon by Dan Aykroyd for some sort of Blues Brothers revival. He got a little boost when an actor portrayed him in Alan Parker's excellent 1991 film, The Commitments, but when his Grammy nominated 2000 album It's Harder Now lost to a Barry White collection, he sabotaged what could've been a career resurgence by sulking and going into seclusion.

Pickett's main problem was drug addiction. Despite some jail terms and time in rehab, he never completely straightened out. He tempered his drinking to a degree, but missed his own induction into the Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame because he was too loaded to show up, denying Bruce Springsteen the chance of a duet on "Mustang Sally."

Fletcher rolls out the whole story, and even stops to tell us about seemingly every musician and recording engineer Pickett ever knew. Granted, a lot of Pickett's sidemen went on to have great careers and cut some interesting singles - some, including guitarist Charles "Skip" Pitts, played on the Isley Brothers' epic funk anthem, "It's Your Thing"- but Fletcher occasionally overdoes it.

"Who are you writing about?" Pickett might ask, holding a gun to Fletcher's ear. "Me, or a bunch of keyboard players?"

Fletcher, a UK writer whose book on Keith Moon is one of the great rock biographies of the past 30 years, seems a little too eager to prove himself a completist. Blow by blow breakdowns of every Pickett album become tiresome, especially when the quotes he uses from Pickett are so succinct and on target. "Baby, I am a mean motherfucker," Pickett said to an interviewer in 1981. "Don't be writing nothing nice, 'cause you be jivin' people."

Fletcher is at his best when he's writing about the high-water moments in Pickett's career, such as the memorable trip to Africa where frenzied concertgoers in Lagos "stared upward at Wilson Pickett as if in the presence of a deity." Or when he recreates the studio session where Pickett recorded "In The Midnight Hour," a song that 50 years later "remains impervious to the thought of improvement." Or when he describes Allman's "intensely pitched licks that exploded like musical firecrackers."

Even so, it's the Wicked Pickett himself who hits the bulls-eye every time, like in the diatribe about disco that he gave to UK writer Nick Kent in 1979: "It's a wretched, puny form of music, but it's the contemporary sound, dig?"

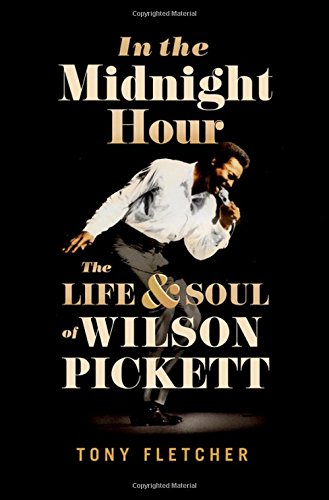

I was intrigued when In The Midnight Hour: The Life & Soul of Wilson Pickett landed on my desk. My first instinct was Cool, I like him, he died in a plane crash, sang "Sittin' on the Dock of the Bay," and all that. But one page into it I realized I was actually thinking of Otis Redding. Still, the two were linked in that Pickett followed Redding's example and headed south to Muscles Shoals to record with a bunch of white musicians who loved soul music. By doing that, Pickett created the songs that still sound riveting today, and sent a message to his audience that white people had soul, too.

Pickett never comes off as likeable in Fletcher's book, but he was one of the first soul stars to play with an integrated band. As he toured the South and introduced black audiences to white musicians, at a time when concert halls were often segregated by seating blacks on one side and whites on the other, he was doing something important. He deserves a biography and a man like Fletcher to write it.

No comments:

Post a Comment