THE EATER OF CHAOS

The Beast of Boleskine Begats another Biography

by Don Stradley

The Beast of Boleskine Begats another Biography

by Don Stradley

Aleister

Crowley always puts me in mind of those shaggy young guys I see working

in comic book shops or, more likely, stores that specialize in Tarot

cards and ceremonial candles. You'll see them at the register, reading

about the occult and Wicca; they wear eyeliner and live on a diet of Taco Bell and Kentucky Fried Chicken; they usually have a chubby,

tattooed girlfriend with a nose piercing (slightly red from infection).

Get to know them, and there's often an allusion to an alternative

lifestyle, usually including some stale bondage gimmick. These people,

with their fetish gear and arcane interests, are distant echoes of The

Great Beast, made insipid by growing up in the generation of YouTube and

X-Box and Swedish death metal. In Gary Lachman's rich new biography of

wicked Aleister, he inadvertently captures the vibe of these outliers

when he describes the young Crowley, "waving his magic wand in front of

his magic mirror, and perfecting an imperturbable stare." The look, you

understand, was all important; however, Crowley at least put his money

where his mouth was, along with hashish, scorpions, and feces.

Aleister

Crowley always puts me in mind of those shaggy young guys I see working

in comic book shops or, more likely, stores that specialize in Tarot

cards and ceremonial candles. You'll see them at the register, reading

about the occult and Wicca; they wear eyeliner and live on a diet of Taco Bell and Kentucky Fried Chicken; they usually have a chubby,

tattooed girlfriend with a nose piercing (slightly red from infection).

Get to know them, and there's often an allusion to an alternative

lifestyle, usually including some stale bondage gimmick. These people,

with their fetish gear and arcane interests, are distant echoes of The

Great Beast, made insipid by growing up in the generation of YouTube and

X-Box and Swedish death metal. In Gary Lachman's rich new biography of

wicked Aleister, he inadvertently captures the vibe of these outliers

when he describes the young Crowley, "waving his magic wand in front of

his magic mirror, and perfecting an imperturbable stare." The look, you

understand, was all important; however, Crowley at least put his money

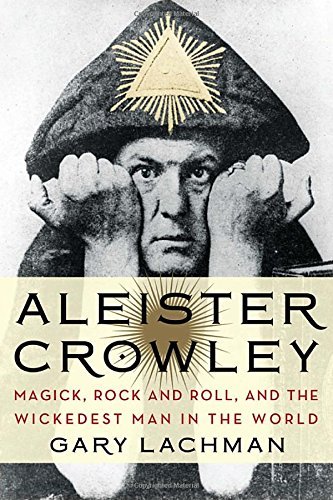

where his mouth was, along with hashish, scorpions, and feces.In Aleister Crowley: Magick, Rock and Roll, And The Wickedest Man In The World, we're shown Crowley in all of his gory glory, and also advised on how to take him. "Nothing would be easier than to dismiss Crowley as an opportunistic fake," Lachman writes, "or to take him at face value as the champion of human liberation." Crowley was, Lachman suggests, "a frustrating confusion of the two." And he did, according to Lachman, have flashes of brilliance, enough to inspire Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page to call him "the great misunderstood genius of the twentieth century." Part of the problem was Crowley's reliance on the trappings of a second-rate bogeyman. One acquaintance described him as a "nursery imp masquerading as Mephistopheles." Still, Lachman boldly compares Crowley to Adolph Hitler. Both, we're told, "fantasized about some master race, lording it over the masses, and both were enamored of the abyss of irrationality that lay latent in the western soul, and wanted to release it."

Crowley's reputation benefits from the number of nervous breakdowns, suicides, and mysterious deaths in his wake. I'm not sure if he really conjured up demons or communicated with astral beings, but it surely was bad luck to be around him. One of his followers, an unfortunate chap named Neuburg, was subjected to an especially sadistic ritual as Crowley "scourged Neuburg's buttocks, cut a cross over his heart, and bound his forehead with a chain." All of this because Crowley was...what? An unhappy child of the Victorian era? A guilt-ridden homosexual who assuaged himself by torturing his lackeys? Lachman theorizes that Crowley suffered "from a kind of autism" and describes him as "a colossal example of arrested development." Once, in a fit of pique, Crowley crucified a frog. And ate it.

Lachman has had an enviable career arc. He played bass in Blondie (under the nom de punk: Gary Valentine) and has carved out a respectable niche as an expert on the occult and magical subjects. He closes the show here with a thoughtful chapter on Crowley's seeping influence on the pop culture, which includes much more than an appearance on the cover of a Beatles album. Still, the fact that Jay Z and Lady Gaga use occult symbols in their videos isn't quite as compelling as the chapters on Crowley's final days as a repulsive old drug addict. It's a bizarre picture, an aging and decrepit Crowley in his tweeds, shambling around London during the war years, cheering the German bombers. Despite some magical ability, which Lachman suggests were legit, Crowley couldn't manifest any money; he died broke in Hastings in 1947. And like most Crowley biographers, Lachman is fascinated by the Beast's weird sex life, like the time Crowley was so inspired by an encounter with a Mexican prostitute that he spent the next 67 hours trying to rewrite Wagner's Tannhauset. One wonders if these glorious Mexican whores exist today, not necessarily for the magicians among us, but for those wanting to take their own crack at Wagner.

No comments:

Post a Comment