RAGE...MURDER...

Authors still getting mileage out of rock's darkest hour

by Don Stradley

My favorite description of The

Rolling Stones comes from Tom Wolfe in one of his early Esquire pieces, back before Esquire

was dumbed down for the internet generation. “They’re modeled after The

Beatles,” he wrote, “only more lower class – deformed.” Hundreds have tried,

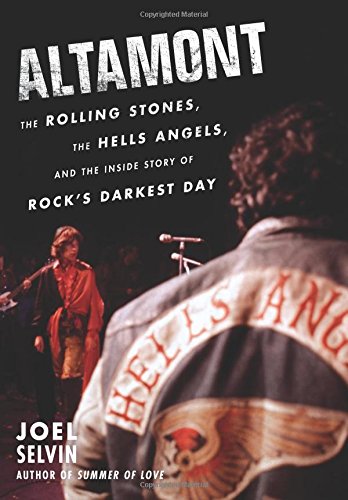

but few have pegged the Stones with Wolfe’s acid pithiness. Joel Selvin comes

close in Altamont, his comprehensive examination of the disastrous free

concert headlined by the Stones, where a local chapter of the Hells Angels

motorcycle club was hired as security. The event is remembered solely because

the Angels’ interpretation of crowd control was straight out of A Clockwork Orange; one audience member,

a gun-wielding African-American male named Meredith Hunter, bled to death after

learning his lime green suit was no match for an Angel’s blade. Since the show

took place in the final month of 1969, the killing served as a bookend for the

decade, “a stain,” Selvin writes, “that wouldn’t wash out of the fabric of the

music.”

My favorite description of The

Rolling Stones comes from Tom Wolfe in one of his early Esquire pieces, back before Esquire

was dumbed down for the internet generation. “They’re modeled after The

Beatles,” he wrote, “only more lower class – deformed.” Hundreds have tried,

but few have pegged the Stones with Wolfe’s acid pithiness. Joel Selvin comes

close in Altamont, his comprehensive examination of the disastrous free

concert headlined by the Stones, where a local chapter of the Hells Angels

motorcycle club was hired as security. The event is remembered solely because

the Angels’ interpretation of crowd control was straight out of A Clockwork Orange; one audience member,

a gun-wielding African-American male named Meredith Hunter, bled to death after

learning his lime green suit was no match for an Angel’s blade. Since the show

took place in the final month of 1969, the killing served as a bookend for the

decade, “a stain,” Selvin writes, “that wouldn’t wash out of the fabric of the

music.”

Though

the band comes off as idiot savants who conjure riffs right out of the

Mississippi Delta but are witless about anything else, they’re served well by

Selvin. He puts the blame for the Altamont mess squarely on their bony

shoulders, but not to where they come off as villains, just typically oblivious

rock stars. For those of us who have seen Gimme

Shelter, the grim documentary where Mick Jagger looked as if he thought he

could control the Angels, or at least distract them, with his hyper dance

moves – watch him during ‘Sympathy for

The Devil’; he’s on overdrive, and it’s not because he’s moved by Bill Wyman’s

bass grooves – and took it as gospel, Selvin clears up a few things, namely,

that the show wasn’t some kind of electrified witches’ Sabbath that went awry.

Rather, it was a perfect confluence of forces not evil but inept.

The

collection of maladroit characters is doled out with Dickensian detail – in the

first chapter alone we meet a menacing drug-dealer with a hook hand known as

“Goldfinger” – and in time we meet every low-rent hustler, hanger-on, and

self-made businessman who thought he could turn a derelict speedway on the

outer reaches of San Francisco Bay into

rock ‘n’ roll manna. As for the Stones, they’d missed out on Woodstock and,

Jagger in particular, felt they’d lost some cachet. What better way to regain

their standing in America than by aligning with the new hip bands of the day,

the Airplane, the Dead, etc.? Jagger, surmises Selvin, thought the Stones could

trump The Beatles, and Woodstock, if they could pull off a big free show for

some California hippies. Why else would he hire a film crew to record the

thing? The Stones wanted a movie chronicle of their American coronation. But

instead of A Hard Day’s Night, they

got the death of Meredith Hunter. How ironic that the Stones, those cheeky

purveyors of all things black, would provide a soundtrack for the fatal knifing

of a black man.

By the

book’s end, Selvin returns to where most of us started, solemnly declaring the Altamont

concert as the hammer that crushed the sixties. He can’t help but be

heavy-handed about it, even suggesting the Stones never again played so

well, an idea I don’t buy. Nor do I go

along with his dismissal of the Angels’ favorite deterrent – the pool cue. I

happen to think the cue is a great weapon – use it as a spear, or a bludgeon,

and if it happens to break over somebody’s head, you still have the short end

to use in close quarters. Selvin, who has covered the pop world for decades, is damn near brilliant during the book’s

first half, recounting the mangy crowd descending on the concert site as “a

malodorous peasant army camping the night before the Battle of Agincourt,” or

the aristocracy’s view of Jagger as “a

social novelty, an exotic beast tame enough to pet.” Even a new stash of

sinsemilla is described with great care, its “fresh, fruity flavor, almost like

tropical lawn clippings.” If only the book’s conclusion, which is as dry as a

court summons, had such flair. I guess the road to damnation is a lot more

interesting than actual damnation.

No comments:

Post a Comment