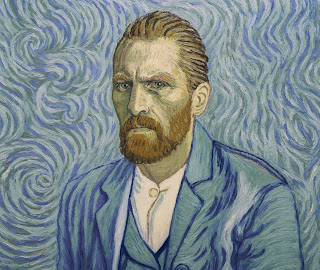

What the team behind Loving Vincent achieves is a mixed blessing. The movie is meticulously handpainted by a 100 or so artists, so the roiling skies and swirling suns depicted by Vincent Van Gogh seem to undulate before our eyes. The living actors are "animated," though animation is too cheap a word for the technique going on here. Their faces undulate, too. Almost to the point of distraction.

Van Gogh not only defined modern art, but set in motion the decades long cliche of the "crazy artist," made concrete by Kirk Douglas' scenery chewing performance in Lust For Life (1956). For many years the lasting image we had of Van Gogh was of Douglas holding his hand over a candle and gritting his teeth, or using a straight razor to slice off his ear. That is, until the 1990s when Tim Roth played the artist in Robert Altman's Vincent and Theo, an underplayed performance which said much about the way the culture had changed since Douglas' day. Douglas looked like he might detonate at many moment; Roth was more insipid, wimpy. I was curious to see how Van Gogh would be depicted in 2017, an era choking on its own political correctness.

I admit that I wanted to see an actor, not a an animated figure, as Vincent. What it all amounted to was something resembling the painstakingly crafted "rotoscope" cartoons developed by the Fleischer studios back in the days of Betty Boop. I also thought of Disney's Snow White, with her delicate gestures and dainty feet. Loving Vincent, of course, is more artful, and more realistic looking, but a cartoon is a cartoon. In a key scene, Vincent stares out at us from the screen; I saw neither madness nor brilliance, only the lifeless eyes of a drawn figure.

I could go on and on about the techniques used to illustrate this movie, but I suggest you see it rather than let me try to explain how Van Gogh's bright stars and angry crows seem to come to life. It was a damn nifty trick, and there was a lot of thought involved, say, in casting the right actors to resemble characters in Van Gogh's paintings. The care that went into the production is admirable - artists on three continents worked on this thing - and will almost make you forget that the movie itself is so thin. Even the announcement at the film's start, which alerts us to the incredible amount of work that went into the creation of Loving Vincent, seems like a bulletproof vest wrapped around the movie. Don't you dare say anything bad about us, it implies, because we all worked so damned hard. In the end, it is a work that seems both magical and rudimentary.

The story centers around Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), the son of Van Gogh's postman, delivering a letter from Van Gogh to his brother, Theo. Vincent has been dead for a year, and the circumstances around his death are mysterious. Roulin, in the manner of Philip Marlowe questioning suspects in The Big Sleep, starts digging around the old neighborhood, trying to learn what he can about this strange painter who committed suicide at 37. Van Gogh's last months are revealed to us in flashback sequences. The painter (Robert Gulaczyk) is seen shambling around, from his rooming house to the wheat fields, occasionally hunched over a canvas, huffing and puffing. He was sometimes seen in the company of rowdy drunks, or fruitlessly trying to chat up women.

I could go on and on about the techniques used to illustrate this movie, but I suggest you see it rather than let me try to explain how Van Gogh's bright stars and angry crows seem to come to life. It was a damn nifty trick, and there was a lot of thought involved, say, in casting the right actors to resemble characters in Van Gogh's paintings. The care that went into the production is admirable - artists on three continents worked on this thing - and will almost make you forget that the movie itself is so thin. Even the announcement at the film's start, which alerts us to the incredible amount of work that went into the creation of Loving Vincent, seems like a bulletproof vest wrapped around the movie. Don't you dare say anything bad about us, it implies, because we all worked so damned hard. In the end, it is a work that seems both magical and rudimentary.

The story centers around Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), the son of Van Gogh's postman, delivering a letter from Van Gogh to his brother, Theo. Vincent has been dead for a year, and the circumstances around his death are mysterious. Roulin, in the manner of Philip Marlowe questioning suspects in The Big Sleep, starts digging around the old neighborhood, trying to learn what he can about this strange painter who committed suicide at 37. Van Gogh's last months are revealed to us in flashback sequences. The painter (Robert Gulaczyk) is seen shambling around, from his rooming house to the wheat fields, occasionally hunched over a canvas, huffing and puffing. He was sometimes seen in the company of rowdy drunks, or fruitlessly trying to chat up women.

He was diligent about his work, though. There's a bit where kids spot him painting in a field and start throwing rocks at him; he simply picks up his easel and canvas and shuffles away, less because of the flying debris, and more because he wants to get on with his art. He painted outdoors even in violent rainstorms. It was as if he knew his time here would be short, and he was trying to get all of his work done before he imploded. We see him writing letters to his brother, asking for money. We see him playing with a little girl, teaching her to draw a chicken. Most people recall him as a clumsy loner, a "tramp." At least one person describes him as "evil," but most think of him as a local eccentric, sort of likeable. Meanwhile, Roulin chases around for witnesses, gets in a few fist fights, argues about the plight of the artist.

As Roulin tries to assemble the pieces of the puzzle, he's baffled. Why would a man touched by genius want to take his life? After all, things were going fairly well for Van Gogh once he left the asylum at Saint Remy. And though he wasn't selling his work, he certainly had his admirers. Then again, he had plenty of bitter rivals who were jealous of his talent, and things had grown stressful with Theo. Like characters in an Agatha Christie novel, everyone Roulin speaks to has a theory behind Van Gogh's death. Not everyone thinks Vincent committed suicide. Some think he was shot in the gut by a local roughneck. The movie wants to leave us wondering.

Ultimately, I liked Gulakzyk's portrayal of Van Gogh, visible even through the animation technique. He doesn't chew the landscape like Douglas, and he's not simpering like Roth. He's a rough, awkward man trying to prove that he's worth something. He had mental problems that could probably be tempered now with lithium, or some other drug. At the time, he was mercurial, prone to deep melancholy and hysteria, balanced by fits of lucidity and energy. This movie, though, is less about Van Gogh and more about the way people saw him, which is fitting for our era of gawkers, voyeurs, and gossip. It puts Van Gogh in a brightly colored fishbowl so we can look on and tell ourselves that we'd be kind to him, suggest he find a good therapist; maybe we'd try to find him a wife on OKCupid. This, I suppose, is the current way we look at madness, as something we can take care of with hugs. Loving Vincent, so full of anachronisms like "nutcase" and "How is that working out for ya?" is Van Gogh's story retold for the Oprah generation.

There is one sublime moment, however, and it is Van Gogh's death scene. He's in bed, bleeding, a country doctor at his side, when the room suddenly washes over in tones of dark blue and grey. There was something in the tableau that recalled Ingres' deathbed scene of Leonardo Da Vinci, where the revered artist is shown dying in the arms of the French king, but with Da Vinci's grandeur and stately bed replaced by Van Gogh's simple room. Unfortunately, the atmosphere was nearly ruined by a version of Don McLean's "Vincent" that plays over the closing credits, a cloying song that doesn't quite reflect a man who saw stars bursting in the night, and skulls smoking cigarettes.

No comments:

Post a Comment