Broken

marriages, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll

Banging a Gong (and

Getting it On) with Tony Visconti

By Don Stradley

Tony

Visconti always struck me as a man of mystery – an exotic sounding name that

often appeared on the liner notes of my favorite albums, he was either a highly

sought after bass player, or a wizard-like knob turner, one that I imagined dressed like Federico

Fellini and worked studio magic for the most magical of recording artists, from

David Bowie and Morrissey, to Iggy Pop, the Boomtown Rats and U2 – but it turns

out there wasn’t much magic to him at all. Which doesn’t mean he was just some

schnook who lucked into a great career as a music producer and arranger; to do

what he did, to help create such iconic titles as Electric Warrior, Diamond Dogs, Scary Monsters, and Heroes, plus an ocean’s worth of art

rock and obscure punk, you’d need enormous

talent, plus the native ability to earn a performer’s trust. Magic? No. After

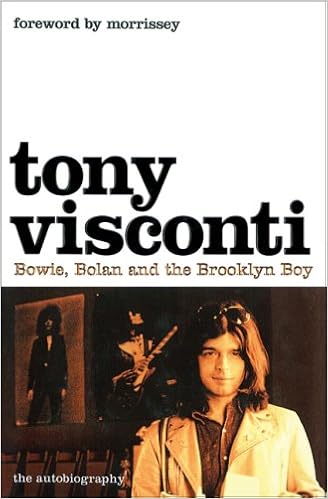

reading Tony Visconti, The Autobiography: Bowie, Bolan, and the Brooklyn Boy (2009, now on Kindle),

I’ll say with confidence that Visconti was no magician but was, rather, a

hardworking journeyman with great ears and incredible patience, the latter

being especially important when dealing with the egocentric world of 1970s

rock.

Tony

Visconti always struck me as a man of mystery – an exotic sounding name that

often appeared on the liner notes of my favorite albums, he was either a highly

sought after bass player, or a wizard-like knob turner, one that I imagined dressed like Federico

Fellini and worked studio magic for the most magical of recording artists, from

David Bowie and Morrissey, to Iggy Pop, the Boomtown Rats and U2 – but it turns

out there wasn’t much magic to him at all. Which doesn’t mean he was just some

schnook who lucked into a great career as a music producer and arranger; to do

what he did, to help create such iconic titles as Electric Warrior, Diamond Dogs, Scary Monsters, and Heroes, plus an ocean’s worth of art

rock and obscure punk, you’d need enormous

talent, plus the native ability to earn a performer’s trust. Magic? No. After

reading Tony Visconti, The Autobiography: Bowie, Bolan, and the Brooklyn Boy (2009, now on Kindle),

I’ll say with confidence that Visconti was no magician but was, rather, a

hardworking journeyman with great ears and incredible patience, the latter

being especially important when dealing with the egocentric world of 1970s

rock.

Early in

Visconti, we’re told that a record

producer “is responsible for every aspect of a recording,” and that “the best

part is when I sit at a mixing console and put it all together.” But traveling

around the planet to work with the likes of Paul McCartney or Thin Lizzy could

fill him with as much frustration as delight, and gouged from his personal life.

Three crumbled marriages, health problems, and enough experiences with heroin

and cocaine to derail anybody – the book has its share of overdoses, suicides,

and even accidental deaths, including one unfortunate drummer who died choking

on a cherry stone – Visconti could easily pat himself on the back for surviving.

What he makes clear is that his love of music is what got him through his most challenging

times. His tone is that of the stranger in a strange land, in awe of his

surroundings, a down to earth Brooklynite who fell in love with The Beatles

and, at 23, hauled ass to London, “the

Mecca of modern pop music,” to learn from the masters.

Visconti

wants to portray himself as a regular guy, but he can’t help but share some

typical rock ‘n’ roll moments, like the time he screwed third wife May Pang

(yes, John Lennon’s ex-girlfriend) on an elevator, or how certain artists liked

to record in the nude, or the troubles he had getting Marc Bolan through a

clawing mob of teen fans. He’s also endearingly candid about some of his

mistakes, such as turning down a chance to produce Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity,’ or

the way he’d once pegged a 19-year-old Bowie as too weird, too “out of kilter

with what was happening on the scene.” Visconti’s slog through the 1980s makes

for painful reading, particularly when new bands began relying on studio

trickery to mask their ineptness. Producing an album for Scotland’s Altered

Images was such a struggle that Visconti writes, “I wanted to take the bass and

guitar out of the group’s hands and play them myself.”

The

final chapters don’t have the crackle of the early sections. His era over,

Visconti practices Tai Chi, studies with motivational gurus, accepts the fact

that he isn’t the marrying kind, and laments that “the music business keeps us

in a permanent state of immaturity.” Still, we read about people like Visconti

to get behind the scenes, and in that regard his autobiography sparkles. Along

with great insights about recording techniques, we get telling snapshots of the

bands of the day. The performers he worked with often come off as selfish, and

unpredictable, but capable at times of unexpected generosity. Bowie, in

particular, became a longtime friend. Visconti, it seems, craved the friendship

of the people who hired him. As I read between the lines, I think he hoped to

be an honorary member of the bands he produced, and felt something like

heartbreak when he was passed over for another producer. Of course, becoming a

de facto band member was no more likely than a midwife hired to deliver a baby would become a family

member. The producer’s job is to nurse

the sound and bring it out into the world,

and few have done it with such passion and innovation as Visconti, never

minding that he was working with people who dressed like elves, couldn’t tune

their own guitars, and behaved like spoiled children.

No comments:

Post a Comment