By

the time I met Goody Petronelli in 2006, the Brockton gym where he had trained

Marvelous Marvin Hagler had seen better days. It was on Ward Street, now

“Petronelli Way.” The block was lonely at sundown, made lonelier by the sound

of empty beer cans rolling across the pavement, and chain link fences rattling

in the wind.

Inside,

the gym was still daunting. It felt hard, unforgiving. The walls were an homage

to Hagler: fight posters from the 1970s, yellowed with age; framed newspaper

clippings; a colorful wall-sized mural of Hagler in his glory. Yet at night,

with no fighters around, the place had the feel of a long-neglected barracks. Intensely

bright lights illuminated the barrenness of the place.

Meanwhile,

white-haired men shuffled in and out of Goody’s office. “If my wife calls,” one

of them said, “tell her I’m not here.” When the phone rang, it wasn’t anyone’s

wife, but a local matchmaker looking for a female featherweight to fill an

undercard slot. After this hiccup of activity, the old gym went silent as a

monastery. The only sound was the humming of an electric clock.

I

was writing a magazine story about Goody, and there he was, sitting behind a

desk, his big-knuckled hands folded in front of him. The walls of his small office

were covered in framed pictures of Hagler, black and white scenes from his

amateur days. I turned on my tape recorder.

“What

do you want me to say?” he asked.

Goody

had a gentle voice and a thick New England accent, giving everything he said a

warm, homey feel. When I told him I had lived in Brockton as a kid, his eyes

brightened.

“You

should’ve stopped by,” he said. “I’d teach you how to fight.”

It

was the kind of straightforward offer that had once caught the attention of a

teenager named Marvin, a sullen boy who simply stopped by one day. He’d been

clumsy at first, with no apparent aptitude for fighting, but he returned a few

days later. He promised Goody he could do better.

“He

was a hard-working kid,” Goody said. “And very precise. Even just lacing up his

shoes, he wanted things perfect. And he learned fast. I’d show him things, then

he’d go home and practice all night in front of a mirror.”

Goody’s

boxing philosophy was simple: take care of the basics. Therefore, Goody schooled

Marvin in the fundamentals. Marvin treated them like holy scripture. Because

Marvin was short, Goody nicknamed him “Short stuff,” which eventually became

just “Stuff.”

Go

get him, Stuff….remember the basics, Stuff…

“I

don’t think Marvin had been around many white people,” Goody said. “One time he

said, ‘Why should I listen to you, whitey?’ My brother Pat and I just laughed

at him. But Marvin got used to us.”

If

Goody was an authority figure, his brother Pat was the playful uncle, sneaking

Marvin a candy bar after a rough day. Neither Goody nor Marvin enjoyed press

conferences, so Pat shined as Marvin’s mouthpiece and became his business

manager. Marvin would later ask Pat to be the godfather of one of his children.

Once, when Marvin was preparing to fight in San Remo, a reporter asked,

“Marvin, how is your Italian?” Marvin said, “Which one? Goody or Pat?”

During

my first visit to Goody’s gym, he handed me a business card. Underneath his

name it read: “The Sole Trainer of Marvelous Marvin Hagler.” He’d had it

made because he disliked the way journalists referred to him and Pat as

Marvin’s “co-trainers.” In fact, Pat was the businessman. Goody was the boxing

man. Goody’s rare distinction was that he’d trained Marvin from the first time

he put on gloves to his final fight. “Be sure to say that in the article,” he

said. “I was Marvin’s only trainer.”

Goody

was 82 when I met him, but he still worked with fighters. He looked frail when

he held the pads for some oversized kid. Yet he was immovable, an old tree

refusing to bend. “Just say I’m 26,” Goody said. “When you tell people your

age, that’s all they talk about.”

I’d

heard a rumor that the gym was struggling. Even those who admired Goody were

doubtful that young fighters wanted to work with a man his age, in a gym that

creaked like an old attic. Goody admitted that business was slow, but he was sure

things would pick up.

Goody

spent most nights in his office with a few of his cronies. They rarely talked

boxing. They talked about Brockton, people they knew, their favorite

restaurants. One of them carried a sketch pad and drew passable caricatures of

fighters. Pat wasn’t part of the gym anymore. Goody said Pat was ill and had

“trouble getting around.” More recently, Goody’s wife underwent an operation

and was home recovering.

“Every

day I look at the front door,” Goody said. “I’m still waiting for another

Marvin Hagler to walk in.”

Yet

there were constant reminders of Marvin. I recognized a cheerful fellow in a

faded red warmup suit as Tiger Moore, one of Marvin’s old sparring partners. He

was pacing around like he was killing time. Marvin’s half-brother, Robbie

Simms, dropped by now and then to do some shadowboxing and work up a sweat. He

drove a coffee truck during the day, so he could only come by late at night

when no one was around. He’d throw combinations in the air, the same combos

Marvin had taught him years ago, when they were boys sharing a bedroom.

The

gym felt like a clubhouse, and these were the last dues-paying members.

At

the end of our first session, Goody raced out of the place with his pals, three

old men sprinting to their cars. It had become a rotten neighborhood.

Guarino

“Goody” Petronelli had fought professionally back in the 1940s, until a broken

wrist forced him to quit. After a long hitch in the U.S. Navy, Goody planned to

open a gym in Brockton with Pat and a friend, fellow Brockton native and

retired heavyweight champion, Rocky Marciano. When Rocky died in a plane crash

in 1969, Goody and Pat went ahead and opened a gym above a hardware store

downtown.

Success

eluded them, even when Marvin turned pro. Talented as he was, Marvin toiled in high

school gymnasium shows and half empty arenas. Throughout this difficult period,

Goody and Pat wouldn’t take a cut from Marvin’s small paydays, saying he could

pay them later. “We knew what we had in Marvin,” Goody said.

During

those lean years, boxing insiders mocked the brothers as rubes holding Marvin

back. Yet the Patronellis were suited to handling Marvin and his many moods. Opponents

often praised Marvin for the accuracy of his punches and his conditioning, the

results of Goody’s old-school methods. And though the Petronellis were unproven

businessmen, Marvin eventually topped Sport magazine’s list of the

highest paid athletes for 1983, 1984, and 1987. Unscrupulous types often

promised him the world if only he’d leave the Petronellis, but Marvin’s bond with

the brothers was shatterproof. Marvin called the arrangement, “the unbreakable

triangle.”

I

wondered if all that money changed Marvin.

“It

wasn’t the money,” Goody said. “What changed him was just fighting for a long

time. When a fighter gets older, he starts to worry about things. For his last

couple of fights, he felt a bit off. That bothered him.”

And

what was it like when Marvin said he was retiring from the business? “I gave

him a hug,” Goody said. “I told him he’d done a good job.”

Goody

must’ve known there’d never be another Marvin but admitting such a thing was

like admitting his real age.

Other

fighters came to the gym on Ward Street. There was a pretty good middleweight who

decided to move to Europe where he thought he’d get more endorsement deals.

There was also a has-been former middleweight titleholder who lived in a nearby

state. His father called Goody and asked, Will you train my son? Goody said

sure, but he’d have to come to Brockton. The caller said thanks but no thanks, as

if Goody’s wisdom wasn’t worth a 40-mile drive.

Just

a year earlier Goody had trained Kevin McBride, an unheralded young heavyweight

who scored an upset win over a faded Mike Tyson. It was Goody’s last moment in

a spotlight. Unable to capitalize on beating Tyson, McBride had vanished from

the scene. “I heard his wife didn’t want him to fight anymore,” Goody said with

a shrug.

Clearly,

Marvin was Goody’s masterpiece. Yet when I tried to steer the conversation to Marvin’s

big money fights with Tommy Hearns and Ray Leonard, Goody gave the impression

that the fun had ended by then. Or maybe he felt enough had been said about

those fights, which he said were “overhyped.” He was happier to talk about the

early years, when each of Marvin’s victories felt like a big one.

I

asked Goody to name his proudest achievement with Marvin. Without hesitation,

Goody said it was when Marvin won the Nationals in 1973.

“To

watch him go from being a chubby 16-year-old to the best amateur in the country

in just a couple years, that was the highlight for me,” Goody said.

With

a hint of regret in his voice, Goody said there was something that bothered

him.

“People

never got to know Marvin,” Goody said. “They knew him as the fighter. But he

was such a great guy. I wish there were more like him.”

When

the magazine story came out, Goody called and thanked me. In all my years as a

writer, he is the only person to do that. This, I imagined, was why Marvin

adored him, why he still called Goody once a month from his home in Milan,

phone calls that I know the old man treasured.

Goody

died in 2012 at 88. Pat died four months earlier. The gym was shuttered in 2011

and has been replaced by an 18-unit luxury apartment complex. Though it’s difficult

to believe, Marvin is gone, too.

On

my final visit to Goody’s office, we talked about Marvin’s induction into the

International Boxing Hall of Fame. Goody was thrilled that the scarlet robe Marvin

wore for his title-winning fight with Alan Minter was displayed in a glass case.

That was the night British fans threw bottles and debris into the ring, and the

Petronellis used their bodies to shield Marvin and hustle him back to the

dressing room. Minter’s fans also broke the windshield on Marvin’s limousine. The

new champion rode back to the hotel sitting on glass shards. On a night they

should’ve celebrated, the little crew from Brockton was dodging bottles and sitting

on broken glass. But they did it together. That was the story being told to me.

It was one of loyalty.

When

I’d set out to interview Goody, I was half-hoping to learn about secret deals

made in the backrooms of Las Vegas casinos, or maybe gain some info about

Marvin’s hard-partying days. Instead, Goody talked about friendship and commitment.

He was still teaching the basics.

And

then we were done, and the lights were turned out, and we all left together.

Behind us was a room with some old boxing equipment, and a mural of Marvelous Marvin

Hagler, gazing out across an empty, cold gym. In 2024, the city unveiled a

statue of Marvin. But it seemed incomplete. There should’ve been bronze figures

of Goody and Pat, too, standing with their champion, the unbreakable triangle

still intact.

* * *

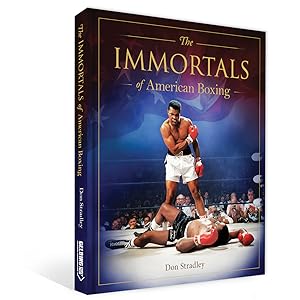

If you enjoyed this article, you might check out some of my books from Amazon. Here is a link to my author's page... https://www.amazon.com/author/donstradley

Thanks!