He was not a crook!

The story of Tricky Dick is still the most intriguing political saga of our time

By Don Stradley

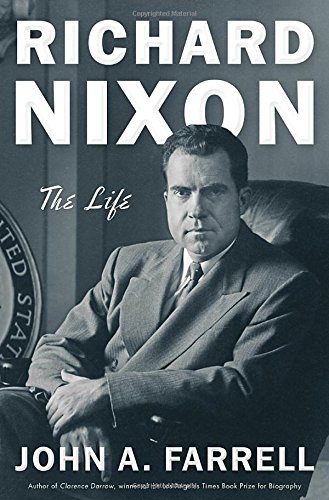

Richard Nixon shouldn't appeal to me - rotten things happened under his watch, the war in Vietnam dragged out for at least four years while he fiddled and diddled, and by most accounts he was a neurotic, petty politician with enough chips on his shoulder to fill a Las Vegas casino - but he does. It's partly because of the image he had in old newspaper cartoons; the five o'clock shadow, the slope of his posture, the sneaky reputation, and the legend that he spent his final days in the White House on his knees praying with Henry Kissinger. He'd started out as a commie basher and spy smasher, but he ended up as Washington's prince of darkness, as if so many years playing on the country's paranoia had turned him more paranoid than anybody. In John A. Farrell's Richard Nixon, The Life, we get a thoughtful, realistic rendering of a complex character. It's a weighty book, 558 pages of reading, but it's a fine, full-blooded account of a man who, like Vincent Van Gogh or Edgar Alan Poe, wore the anguish of his calling. Nixon wore it on his face and in his bones.

Late in the book, we're given a quote by Kissinger: "It was hard to avoid the impression that Nixon, who thrived on crises, also craved disasters." A recurring theme in this insightful biography is that Nixon courted controversy, and gambled on himself to overcome his own self laid booby traps. As one insider put it, Nixon was like any gambler, and "the thrill was in those few breathtaking moments when the dice were in the air." The observations, plucked from decades of Nixon-based literature, add up to Nixon being diabolically smart, surprisingly progressive in many ways, but always digging holes for himself, partly because he firmly believed he was too intelligent, too tough, to fail. He swung hard, for the fences every time. "A man who has never lost himself in a cause bigger than himself has missed out on one of life's mountaintop experiences," Nixon said. "Only in losing himself does he find himself."

What exactly did he find? And did he like what he saw? "It's a piece of cake until you get to the top," he once said of a political career. Then, in words that may as well be describing a man with a gambling addiction, Nixon added, "you continue to walk on the edge of the precipice because over the years you have become fascinated by how close to the edge you can walk without losing your balance." He was the wiliest of political animals, a diabolical thinker who was always two or three moves ahead of everyone, yet what should have been a great presidency was derailed by a quick series of stupid mistakes and bad choices.

The key scenes and characters play out like parts of a crazy, kitschy, American opera: there's Pat Nixon, the long suffering wife; Alger Hiss; Joe McCarthy; Checkers the dog; Eisenhower, the mentor and ball buster; John Kennedy, a friend, then a foe; the '68 comeback; thousands of burned and butchered bodies strewn across the jungles of Vietnam; Nixon in China; Nixon in Russia; the hiring of Hunt and Liddy, the "sycophants and klutzes" brought into the White House to run Nixon's black ops; and the disastrous coverup of the Watergate break in, a stunt no worse than what we've seen since from other presidents, but because Nixon had broken so many backs on the way up, he was too unlikable to get away with it. Nixon wanted to be a giant, and he very nearly was one. And he did it during one of the most turbulent eras in our history, navigating some incredibly bumpy terrain, while secretly despising the political life, the smiling and the handshakes and the phony dinners and soirees, and people like Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, panned succinctly by Farrell as "a Kennedy coat holder."

Farrell doesn't gloss over Nixon's cold-blooded style, for if Nixon was a brilliant politician who could survey any scene and understand what was needed to get votes, he was also a ruthless mauler of any perceived enemy. There's a jaw dropping opening scene where a 33-year-old Nixon, fresh out of the U.S. Navy, is asked by a Whittier California group to run for Congress. He immediately suggests that spies be sent to his opponent's camp. With his first political breaths, he'd revealed himself to be a willingly dirty player, and set the course for one of the most controversial political legacies in history, one that Farrell has set down with fairness, compassion, and style.

Still, it's Nixon who has the best lines, like when he tells H.R. Haldeman, "If I'm assassinated, I want you to have them play 'Dante's Inferno,' and have Lawrence Welk produce it."

That's my Nixon; hellfire and waltzes.

No comments:

Post a Comment